Desert Dwelling at Taliesin West

There is a long tradition of experimental housing at the School of Architecture at Taliesin (SOAT), formerly known as the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture. When Wright and his apprentices started Taliesin West in 1938, the apprentices slept in pyramid-shaped canvas tents over concrete slabs and “desert masonry” bases, scattered throughout the desert at the base of the McDowell Mountains in what is now Scottsdale, AZ.

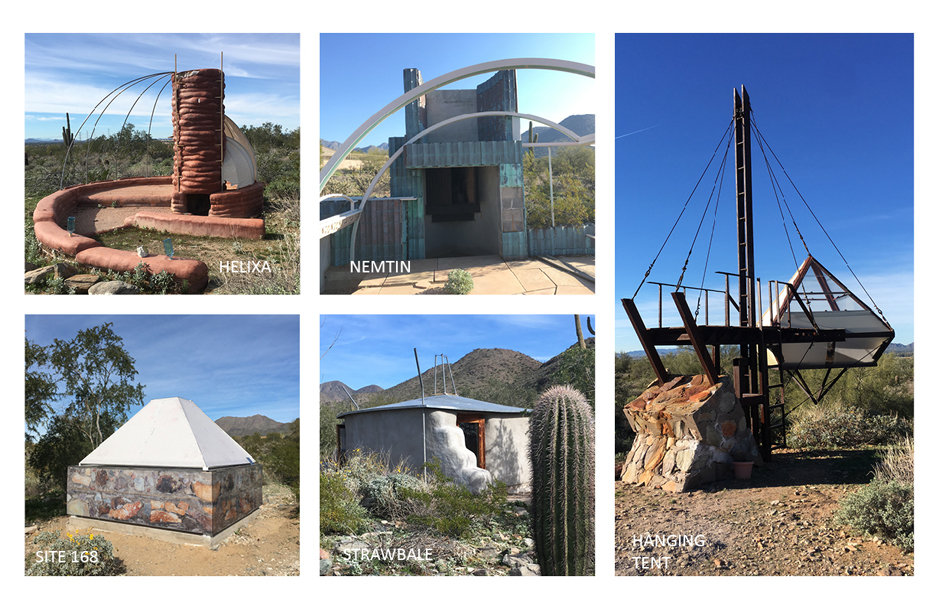

Today, approximately 20 M. Arch students reside in the locations of their predecessors. The shelters have evolved from simple shepherd’s tents to a wide array of experimental structures, but they’re all required to be located on the historic sites. Many make use of the low desert masonry walls, which have outlasted the canvas by decades, to create new forms of shelters.

Under the leadership of Aaron Betsky, dean since 2015, SOAT plans to expand to 60 students within a few years. However, fewer than 25 habitable shelters currently exist on the property. At a rate of 5-7 students completing a new shelter each year, there soon won’t be enough housing to meet demand. Temporary group housing could offer a solution ̶ the school would have enough beds to grow their student body now, and later repurpose the housing structure when enough of the approximately 75 sites are developed for each student to have their own shelter.

This past January, I spent four weeks at Taliesin West, sleeping in the desert shelter known as Hanging Tent. Built in 2001 by Fatima Elmalimpinar and Fabian Mantel, Hanging Tent takes the basic form of the shepherd’s tent, and suspends it several feet above the desert floor. It was a beautiful place to watch the super blood moon through the (retrofitted) acrylic roof, but that same clear roof made it too hot to occupy during the day.

Mornings, I meandered along a small path past other shelters, both functional and not. Walking through the desert at Taliesin West gives you a glimpse into its history: so many projects exist in a kind of unfinished limbo. I picked up about 1,000 rusty nails hidden among the cholla cacti. Finding nails became a meditative practice and an exercise in seeing. Each time I thought I’d picked up the last nail in the desert, more would suddenly appear when I refocused my eyes. With every nail I’d wonder: what did this once hold together?

My biggest find was a 20”x30” piece of bullet-ridden rusty steel, with only trace remnants of what I assume was sign enamel. I imagine it once menacingly declared “No Trespassing.” To transport it to the historic drafting room where I worked, I slung the sign over my shoulder with a rusty post. With the sharp bullet-exit side of the sign facing out, I was armored like many other desert-dwelling life.

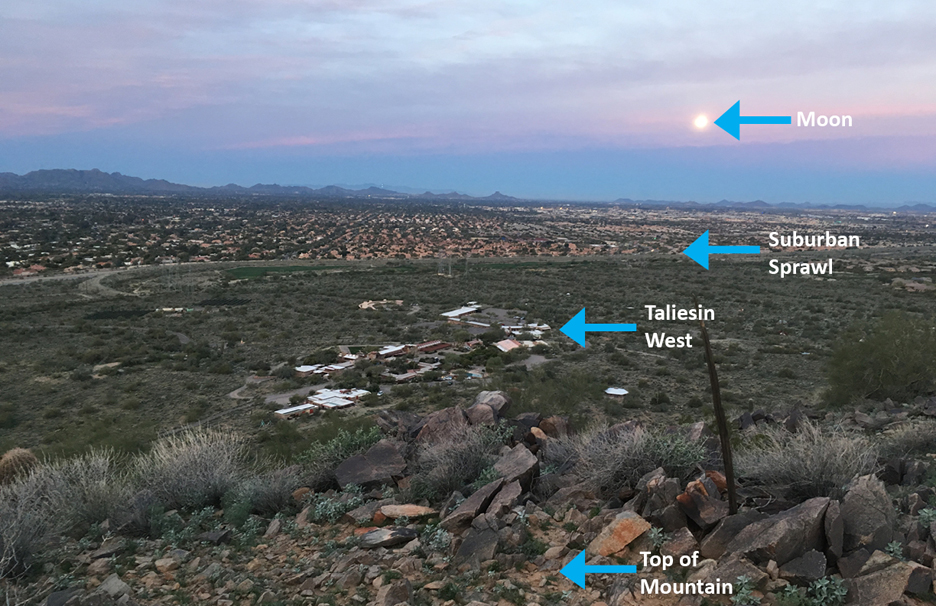

This landscape doesn’t exclusively favor history. A watchful eye can also find items of a more recent provenance. When Frank Lloyd Wright and his apprentices first came here, the site was more-or-less open desert. Now, the edge of the property is clearly visible with luxury developments pressed right up to the property line. Wind carries in detritus from the suburbs, like garishly shiny Mylar balloons. A big silvery number “3”, perhaps from a kid’s birthday party. A cyan glint that caught my eye through the scrub turned out to be a blue pentagonal balloon.

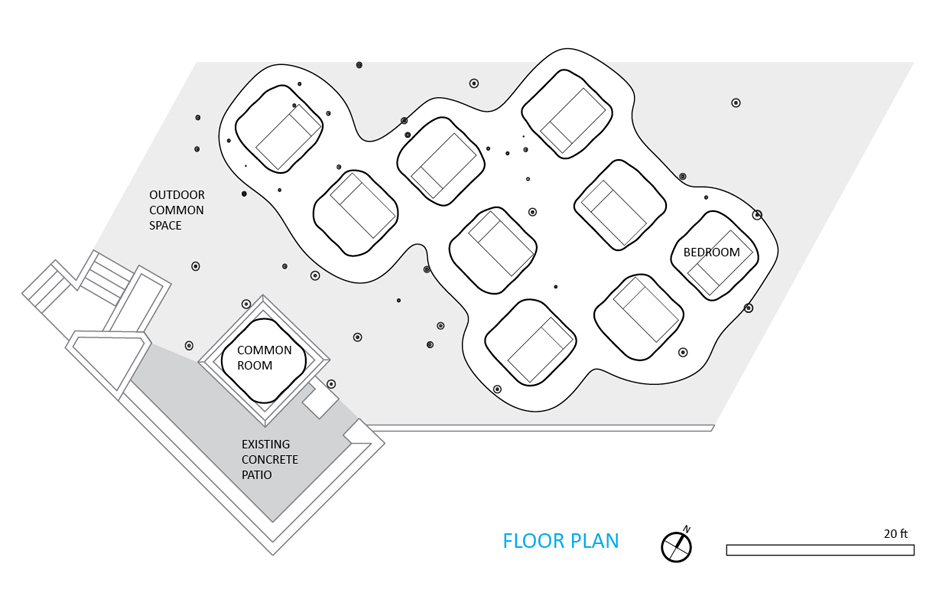

I’m interested in this space where old and new converge. To that end, I created a model for student housing based on the interaction of historical and contemporary elements. My proposal redevelops a site that formerly showcased a prototype of a mobile home. Because of this, there is power on site, and running water nearby, amenities that are nonexistent at other shelter sites. There’s also a large red concrete pad, and a Falling Water-esque concrete patio cantilevered over a deep wash. I’m proposing to demolish the concrete pad and create temporary housing for 10 students.

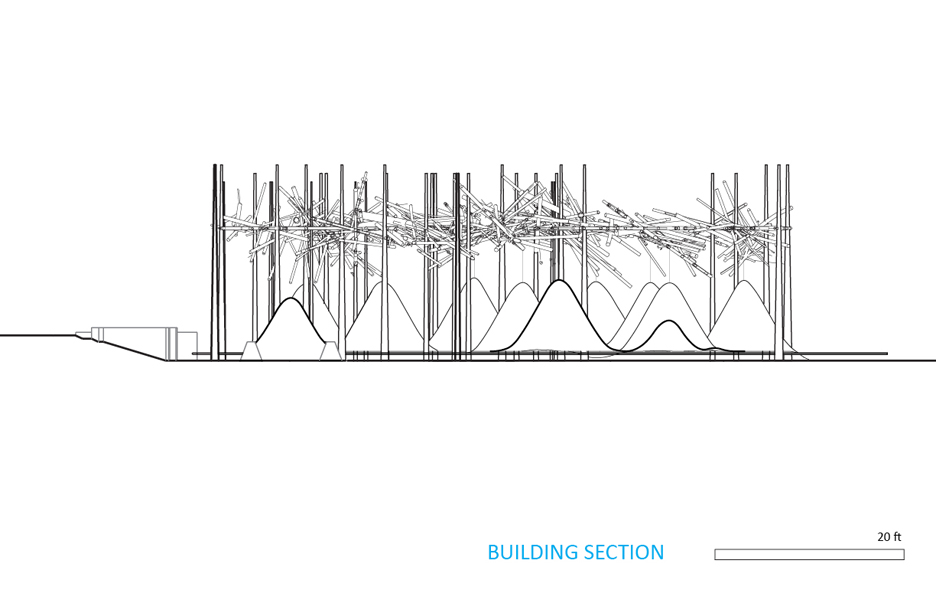

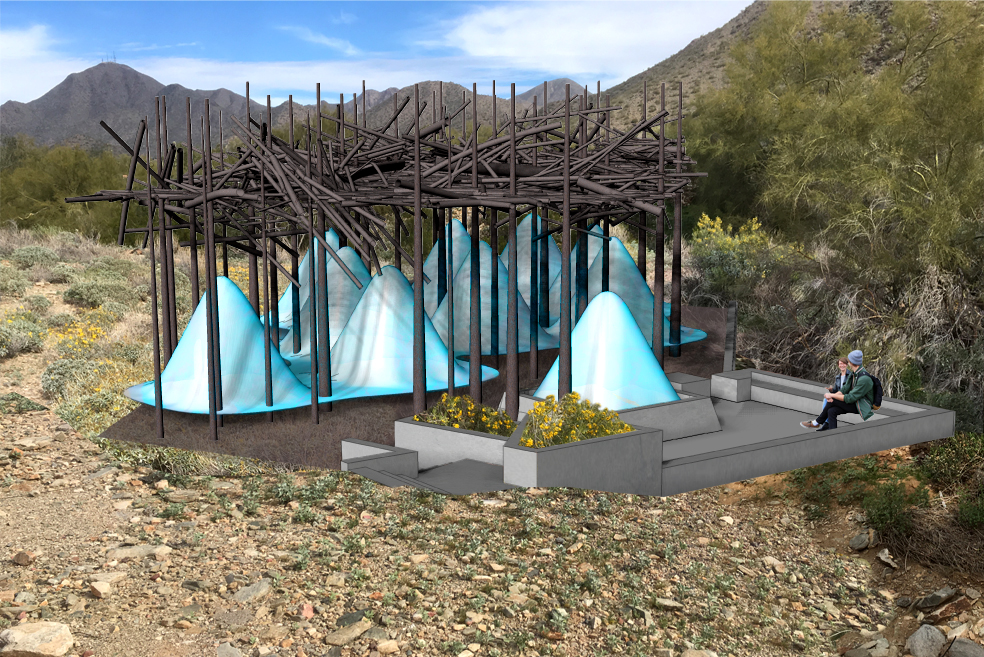

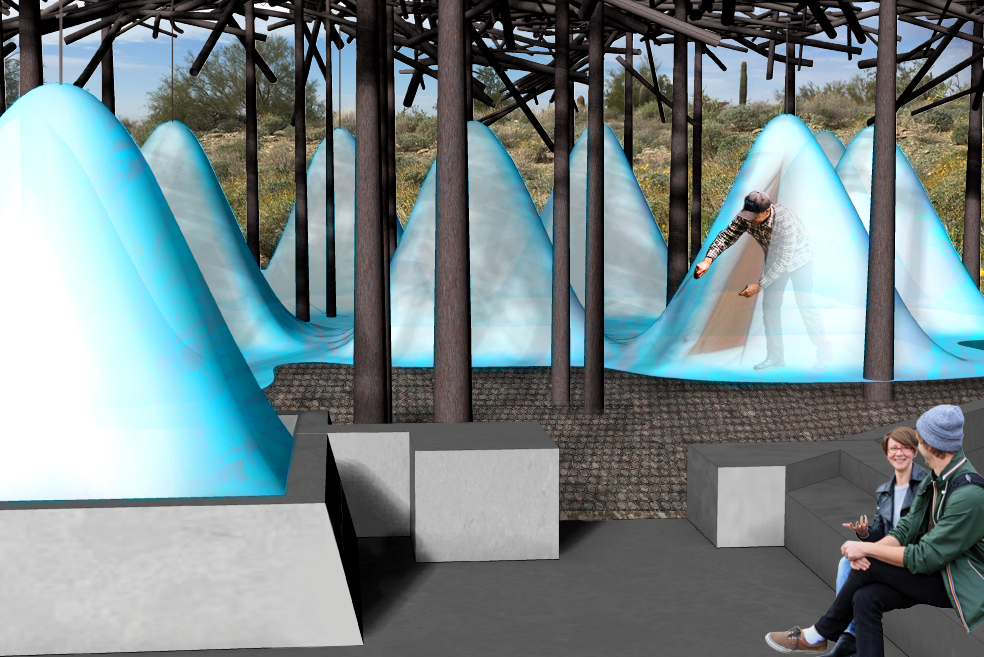

This housing structure would offer shade and physical protection, and contain flexible interior tents to shield occupants from wind and rain. The shade structure is made of steel pipes of varying sizes, arranged as if a giant emptied a bucket of nails into a big jumble. Some of the pipes simultaneously act as the foundation (as friction piles), the columns, and as vertical shade elements. Other smaller pipes provide shade and the infrastructure from which the tents are suspended. The canopy of pipes is as deep as it is wide, with all the pipes at different angles in order to provide shade no matter the angle of the sun. The effect is like a saguaro cactus housing the Gila woodpecker: a spiky uninviting exterior, with a hospitable interior.

In place of the red concrete pad, the floor would be a circular pattern metal grate, held several inches above the desert floor to allow for plant re-growth, and keep students protected from crawling critters. The occupiable interior space has a floor of the same material as the tent, over the metal grate. Future utilities could be fed from below, further increasing the flexibility of the space.

Ten bedrooms would be made from one piece of translucent PTFE membrane, suspended from the shade canopy above. The existing patio and tent site will be used as common space. The rooms themselves are the standard size shepherd’s tent, which provides just enough space for a twin-size bed, night-stand, and floor space to maneuver. SOAT students don’t need more than a place to sleep because all schoolwork happens in the studio, and locker rooms are provided for storage and bathing. The membrane could be blue to lull students to sleep, or white with varying levels of transparency in order to see a glimpse of sky through the lattice of the canopy.

The first shelters at Taliesin West provided a lasting stone and concrete infrastructure for canvas tents, which could be removed and replaced as needed. My proposal for new student housing takes the same idea a step further. By providing shade as part of the infrastructure, students can use their rooms even during the hottest part of the day. There’s also a greater level of flexibility because, when the immediate need for more housing is met, the single membrane can be re-tensioned to form space for the future needs of the school.

For more information about the School of Architecture at Taliesin West, visit: https://taliesin.edu/