Architects, Drop the “Catalogue” Mindset and Specify Locally Sourced Timber

PUBLISHED: FEB. 1, 2024

Growing up in a mill town in Northern Idaho, I could hear the low rumble of lumber mills along the Spokane River as I fell asleep. There were seven mills downriver of Coeur d’Alene then. Now, there are none. As one mill after another shut its doors, the community grappled with the loss of this vital trade and the jobs it supported, shaking its fists at the economic forces seemingly so far beyond our control. At the same time, I saw new buildings in Coeur d’Alene being constructed of brick, with steel structures and glass facades, materials shipped in from across the globe, with no discernable connection to our community.

This pattern was mirrored globally as the industry pivoted to steel and concrete, sourced from afar without regard for the resources available locally. This change has had significant repercussions, destabilizing local trades and contributing to environmental degradation through increased carbon emissions and resource depletion. This way of sourcing materials has resulted in a building stock wholly divorced from its local environment.

In recent years, we’ve started finding our way back through the re-acceptance of wood as a viable building material. Industry leaders, through advocacy and research, have proven wood’s viability — highlighting its strength, fire resistance, and environmental benefits.

True transformative potential, however, lies one step further, in embracing locally sourced wood.

No single strategy will positively impact the architecture profession more than simply considering where our building materials come from. From energy efficiency to carbon footprint to longevity and health of buildings, locally sourced materials offer the greatest potential to return to a timeless way of building.

No single strategy will positively impact the architecture profession more than simply considering where our building materials come from.

The Case for Locally Sourced Wood

When sourced from sustainable forests, locally sourced wood materials not only avoid carbon emissions from cross-continental shipping, but they can also have a climate positive impact by storing carbon in the wood. Economically, this practice supports local jobs and trade economies. Even in places where these trades are struggling, the choice to use local trades whenever possible will boost those economies over time. It also makes sense from the owner’s point of view: while costs may be comparable to other building materials, prefabricated wood solutions like cross laminated timber can save money by shortening construction time.

In my practice, I’ve found that locally sourced wood brings a unique warmth and character to buildings, grounding them in their specific landscapes. Whether it’s a building in the rolling hills of Santa Cruz or along the vibrant shores of Seattle, local materials anchor a structure in its setting, creating a special sense of space.

Making It Happen

The shift back to local sourcing requires a fundamental change in mindset. It’s about looking beyond the pages of a catalogue and taking stock of the environment that surrounds us.

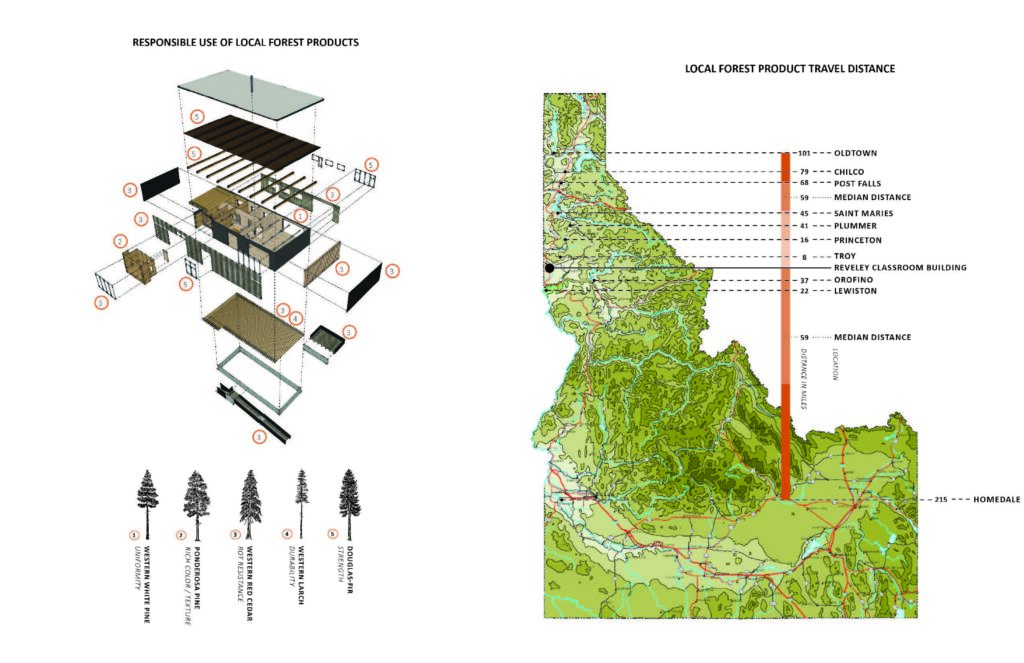

This was a lesson I learned while working on the Revelry Classroom Building at the University of Idaho. Our client was adamant that only Idaho forest products could be used in the creation of this building. This reframed the specification process for me, forcing me to look around to the natural forests and manufacturers. Working in collaboration with Idaho wood industry partners, our design team used locally produced wood materials throughout, including FSC- and SFI-certified framing lumber, cedar siding, engineered wood I-joists and glulam beams. We harvested Western Larch from the University of Idaho’s experimental forest, dried it in university kilns, and milled it for the flooring. Interior walls were clad with veneered wood panels, each highlighting a particular Idaho wood species. In the end, our materials traveled an average of 70 miles from source to project site.

Building relationships with local manufacturers and mills is crucial. By understanding the qualities of each material, designers can make informed decisions about their use in different aspects of a project.

At EHDD, we are forming partnerships with regional mills and west coast-based mass timber fabricators to highlight the value and potential of our locally produced materials. We’ve had success specifying local materials on both public and private projects; while publicly bid projects require more rigor to source multiple options for materials, it can be done, and done within budget.

Our Western Yacht Harbor project in Seattle exemplifies this approach. As Seattle’s first modern Dowel Laminated Timber (DLT) building, we put in the time to build connections with local manufacturers and better understand the characteristics of their materials. The use of hardwood dowels in DLT not only reduces the carbon footprint but also provides a stable, resilient structure, perfectly suited to Seattle’s commitment to innovative design.

In another example, EHDD recently designed the UC Santa Cruz Coastal Biology Building, a new 40,000 sf building serving the university’s world-class marine and ocean health research, education, and public service facility. Located along the Pacific Coast, we sought local timber that could withstand the harsh coastal climate, while exemplifying the region’s character. Working with local manufacturers, we learned about Western Red Cedar, which was used on the exterior. This material is a defining characteristic of the final building and will serve the university for years to come.

The journey back to local sourcing in architecture is not just a nod to the past—it’s a necessary step toward a sustainable future. By reconnecting our buildings with their local roots, we create spaces that are not only environmentally responsible, but also deeply resonant with the communities they serve. As architects, we have the responsibility to lead this change.

As EHDD CEO Jennifer Devlin-Herbert at the 2023 AIA Keynote Panel, “architects control the spec book.” It’s not just about specifying wood; it’s about knowing where the trees were grown, who milled it, how far was it delivered? These questions, when applied to all building materials, will move us toward more sustainable building projects, positively impacting our communities and regions.