Architecture and Social Media’s Effects

Unlock, Snap, and Post is all it takes to share images or content in today’s digital age. Three easy steps and the online world is at your disposal. Tagging people and places associates them with your digital footprint. This content is then readily available at your fingertips within seconds, whether it be a dog wearing a Pikachu outfit or global events that will define our moment in history.

But, what does all of this speed and access to information mean to the world of architecture? These new technologies and behaviors have made the consumption of architecture unlike ever before. Gone are the days when the architect dictated how and where the process of architecture happened. The role is evolving, and there is an ever-increasing control in the user’s hands. Take for instance pop-up architecture like the Museum of Ice Cream and the Color Factory, the ultimate destinations for any millennial. The attraction here for youth is the numerous possibilities to be able to take those memorable Instagram pics.

Architecture here is very much pulled apart; what one is consuming and distributing is based on the likelihood of an audience liking and sharing your photograph. And what this, in turn, allows is the increasing popularity of the physical site with a particular experience, one that is of smiles and bliss. Numerous landmarks have become associated with this phenomenon, where Instagrammable locations just become part of a tourist’s checklist like San Francisco’s Lombard Street.

How do we create architecture today, when structures are being consumed faster than they are being produced? Do Instagrammable features need to be an increased part of architecture or are they the direct byproduct of producing architecture in the age of technology? We do have to acknowledge that this has flipped the grounds on the traditional publication and consumption of architecture, but then also does this mean that we are losing control over what we produce?

There is an increasing demand to produce buildings and spaces that invite this type of online popularity. These conditions give the Architect less agency; they are not able to fully design the spatial experience as they need. However, a direct result of this new trend has been that we can gain critical feedback on the go while exploring beyond traditional building typologies. This surplus of information can be used to engage with audiences unlike ever before. Social media allows individuals to express themselves without a filter – this brutal honesty from the community is less likely to be heard in a public forum or meeting. Such data can be used by designers to better understand what users demand. In this way, we can use the power of social media to our advantage and still address critical issues like climate change and sustainability, while also making “photogenic” architecture.

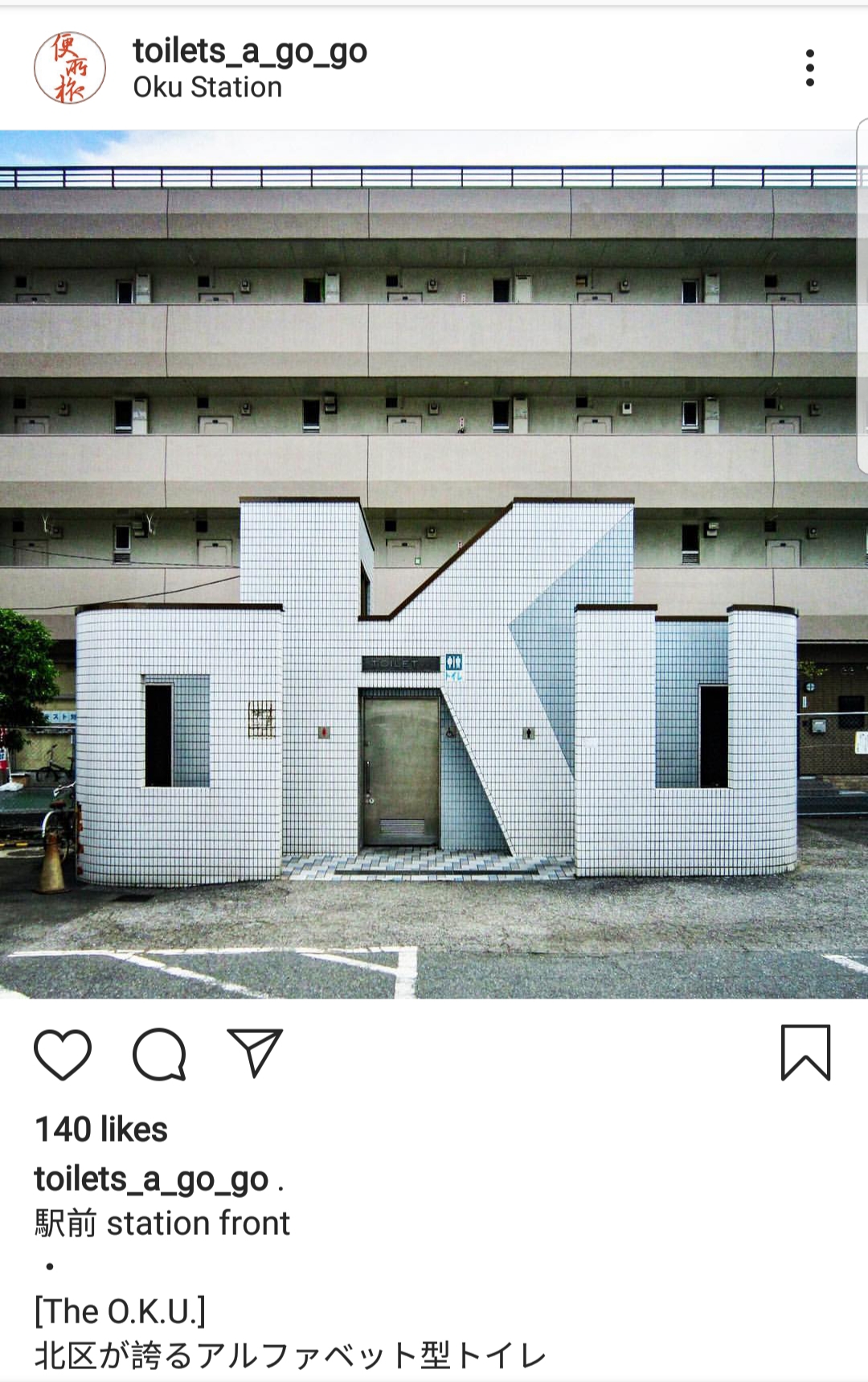

A few weeks ago, I stumbled upon the Japanese Instagram Page “Toilets-a-go-go” which shows images of public bathroom pavilions. Once you get past the funny and somewhat misleading name, this page brings something new and unique to light. In the west, public restrooms and facilities are often considered of minor importance and aren’t seen as the most desirable buildings to design. But what this page allows for is the power of architecture to improve a neglected, yet arguably important building type, while facilitating continued experimentation.

The power of social media is only increasing; every day millions of individuals are able to access an online world that was not available to them the day before. Architecture is quite literally “spreading” through social media. As a result, designers gain greater access to inspiring precedent images and essential insight into global trends. But does this mean that we need to partake in every single fad that follows, or will we be selective and critical of the buildings and experiences that we create?