Is More Meaningful Architecture Possible? A Reflection on Parrhasius’ Veil

One of my favorite parables is about two rival painters. It takes place in the first century, in Athens. Zeuxis and Parrhasius are each thought to be the greatest artist in the classical world. Yet, each is celebrated for very different reasons. Zeuxis is widely known for his consummate technical skill, while Parrhasius is known for his deep understanding of human nature. Eventually a duel is arranged to settle once and for all who is, in fact, the greater artist. When the day of the duel arrives, a large crowd gathers. Unabashedly, Zeuxis unveils a painting of grapes so realistic that birds began to swoop down from the sky and peck at them. The crowd cheers. And, confident of his victory, Zeuxis approaches Parrhasius’s painting to grab the veil covering it. Yet to everyone’s amazement, he touches only canvas. Parrhasius had in fact painted a veil. Bewildered, Zeuxis immediately admitted defeat.

The story of Parrhasius and his veil is memorable because it suggests the power and efficacy of an artist’s concern for the human being and human experience over technical novelty. Though Parrhasius must have painted with great skill to bluff Zeuxis so effectively, his work of art was not the painting itself. It was the human response. His work of art was not the physical paint and canvas, but Zeuxis reaching out to touch it. That experience is what created its meaning. That was the art. And that revelation, I think, is why Zeuxis so quickly admitted defeat.

There is a tendency for architects to believe that the buildings we design, like Zeuxis’s grapes, are an end to themselves. That they should capture people’s attention with their technical wizardry or formal novelty. That the spectacle of it all might somehow create meaning. Perhaps akin to looking through a kaleidoscope. You cannot help but be mesmerized by buildings like this, yet eventually realize beneath the surface there is little depth or substance. It is all rind, and no fruit.

The lesson Parrhasius offers is that more meaningful architecture is possible. And it does not begin with the fantasizing of spaces, but with a deeper awareness of human nature. Not with a formal imagination, but with an empathetic one. With an emotional intelligence, with ideas endorsed by feeling and lived experience. And an understanding of all the many human events and daily rituals of life (even the most mundane) that as a whole give richer meaning to our lives.

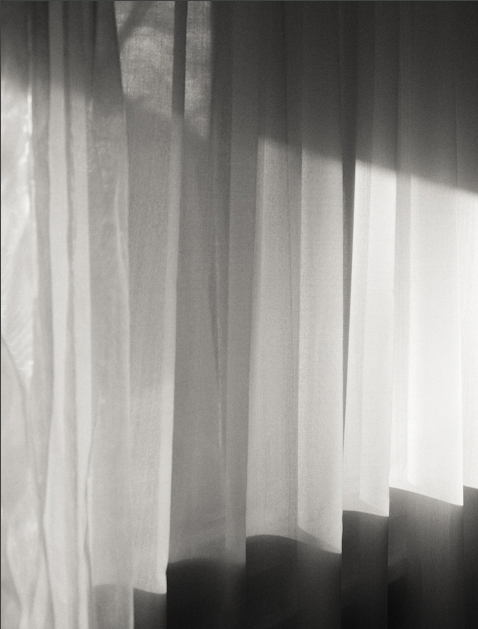

It is a way of thinking that requires constant discovery, to uncover not only the physical reality and history of a place, but also the multiplicity of people and experiences that might occupy it. Eventually, an architecture might emerge that is a more genuine expression of its inhabitants and its place. One that is not held together by its exterior figure, rather, by a rich and layered sequence of atmospheres. It is more meaningful and real, and like Parrhasius’s veil, that relies on each of us to reach out and experience it directly.