Blog Archives

Design for All

With Thomas Kinkade’s recent death, the controversy regarding his status as an artist surfaced once again, reflecting the vast difference in the perception of art between the professional establishment and the general populace. That same divide can be seen in architecture. As architects, we’re always pushing for better design; however, we’re often met with resistance from clients who may not value or understand Design with a capital ‘D’. It is often seen as arbitrary, subjective, elitist, the list goes on.

A big cause of this is that our clients and projects have changed drastically over time. For the majority of history – starting with the church and followed by private patrons like the Medicis or Familia Guell – only the rich, powerful and educated elite hired architects and served as their patrons, because they understood the importance and value that architecture can bring.

Very few of us now have patrons, and even if we do have repeat clients, they may not be rich or powerful. Our “clients” include institutions, stakeholders, users, neighborhood associations, activist groups, basically anyone who we may need to convince to move a project forward. Often these people do not have any kind of formal design education, so their appreciation of how architecture can work for them may be limited.

Also, architects used to design only significant projects. Everything else was built by craftsmen, and there was a distinction between design and craft. However, the onset of codes and regulations of the last century has eroded the distinction and changed the business model. Now our projects range from basic grocery stores to highly designed museums, but with a lot more of us working on the former while wishing we could be designing the latter. The reality is that design is not always prioritized and often misunderstood as part of our services.

Yet even with this considerable shift in client and project types, architects have done little to really address this growing gap between the public and ourselves in terms of understanding the benefits of design. This lack of public awareness is also why architects are often glamorized, but architecture is then ultimately devalued.

In a society where art education is already in a constantly precarious spot, there’s obviously no room for general architectural education. While I’m definitely not advocating for some watered-down architecture overview, I do believe that design should be part of everyone’s education. And I would also like to make the stand for abolishing undergraduate architecture degrees in favor of establishing more general design programs to catch a wider audience.

While many people think that design education is about trends, styles and aesthetics, it offers so much more. Design should be taught because it is relevant, universal, accessible and enhancing. Some of the most important design skills: critical observation, research and analysis, creative problem solving, visioning, asking “why not?”, do not just lend themselves to advancing the aesthetic and physical world around us (the next coolest chair, the impact font of the year), but can have an enormous force on the world of business, social policy, law, and science.

Another worrisome factor is the significant drop-out rate of architecture students after their freshman year and even after their graduation. So instead of teaching architecture in such a narrowly defined trajectory, hoping that a small percentage of students will succeed, why not open design to more people as a general education, which they can use to springboard into a broader array of future professions whether it be architect, rocket scientist or CEO? The realization of the value of a design-integrated curriculum is a trend that’s already started: CCA offers a Design/MBA program, while Stanford has a d.school. Furthermore, design thinking spreading beyond traditional design professions has already been pioneered by IDEO and has been followed by other design think tanks like AMO or VisionArc.

If more people understood design and its advantages, then there’s a better chance that we’ll have better clients. And if we have better clients who appreciate design, then architecture would be so much richer (even if architects are not). It would take design out of the vacuum of pure architecture, and allow the conversation to be much more involved. And architectural failures, whether it’s the everyday strip mall, grocery store, or famous ones like Pruitt-Igoe may have had a better chance for success because instead of ineffectively talking to our clients about design, we can talk with them about its realities and opportunities.

In the end, one thing remains consistent throughout history, there’s always more demand for a grocery store than for a museum. So wouldn’t it be great if that grocery store owner understood what design can accomplish?

SiJing Tan Sanchez, LEED® AP

Architect

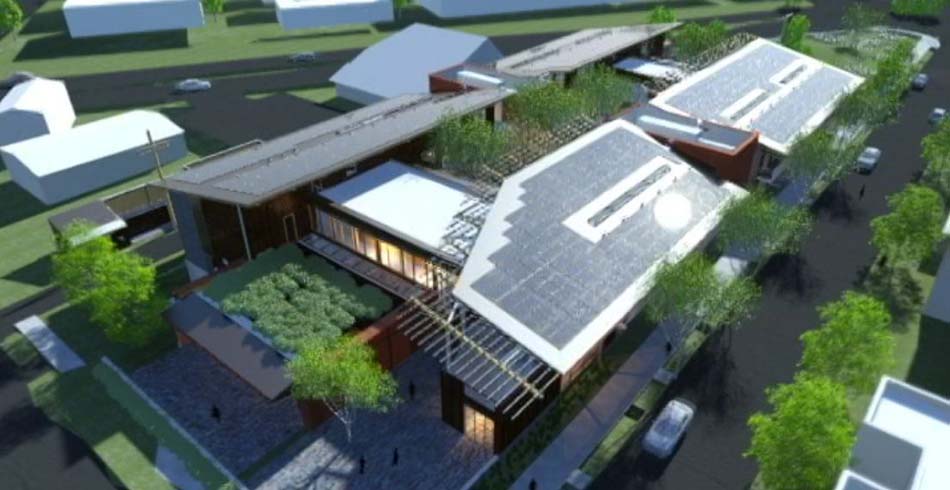

Lands End Lookout

When you stand on the promenade at Lands End gazing out at the Pacific Ocean it feels like, if you could look far enough, you just might see the other side of the world. And if you lean over the edge, the wind almost supports your weight as you study the crashing waves and the ruins of Sutro Baths a hundred feet below.

The landscape is wild, but the Cliff House clinging precariously to the edge of the world is a testament to man’s repeated attempts to tame it. In fact, this struggle is the main interpretive theme of the exhibit housed in the new Lands End Lookout visitor center: “Here at Lands End, you are at the edge of the continent where the intersection of people and natural forces continues to change this wild landscape as they have for thousands of years”. As you start to explore the surrounding national park, you realize that the line between nature and culture is blurred everywhere – in the “natural” cypress forests, and rock cliffs of Sutro Heights Park, in the Stewardship program that collects seeds native to the watershed and tends to the restored natural habitat, and in every story of the site’s rich history.

This struggle between culture and nature is perhaps most evident in the ruins of Sutro Baths, where the remains of a huge man made structure have been reclaimed by nature into a thriving brackish marsh. The design of EHDD’s new building is inspired by these ruins – formed from a series of concrete walls that rise up out of the landscape to organize the building components and frame views. Across the grain of these walls, glass planes and reclaimed redwood siding reference the vernacular and monumental structures of the site’s past amusements – the steel and glass of the baths, but also the oyster and chop houses of Merrie Way.

While the building aesthetic references the ruins, its design is also inspired by the design of the original baths. Adolph Sutro was an engineer who made his fortune inventing a system of water and air delivery for the silver mines of Nevada. When he relocated to San Francisco, he recognized a unique opportunity in the bowl of the former Naiad Cove, choosing the site for his large public baths. Using the existing geology he captured the waves and through a series of tunnels and settling basins, used them to passively feed the pools of his new baths.

Similarly, the design of the Lookout takes advantage of the naturally prevailing winds and the existing topography of the site to passively ventilate the building, bringing air in low – below the floor – and exhausting it high through the clerestories above. This strategy helps make the building 32% more energy efficient than the ASHRAE baseline. It also creates a sunny wind-sheltered courtyard on the leeward side, providing a rare respite from the harsh environment for those exploring the trails and beaches of Lands End.

And, similar to Sutro’s use of wind power to pump water to his gravity fed irrigation system, solar panels on the Lookout roof help offset an additional 32% of the building’s remaining energy needs (making the overall efficiency 53% better than baseline). While the building takes advantage of many new technologies – efficient LED fixtures, lighting controls, energy star appliances and high performing glass, and insulation – it’s the natural ventilation and daylighting strategies that really make a difference.

I like to think about Adolph Sutro gazing out from his terrace, past the sculptures and his baths below, to the distant horizon. He’s wondering how to rebuild his Cliff House – after yet another devastating fire – this time out of concrete instead of wood. He never would have imagined that his ideals – of popular access to recreation and innovative efficient use of natural resources – would be echoed in a National Park Service visitor center on the site over a hundred years later.

Similarly, I can imagine EHDD’s late founder Joseph Esherick, standing on the edge of the continent a bit further north at Sea Ranch. Leaning into the same wind, he’s grappling with how to site the now iconic Hedgerow houses. It’s so satisfying, to learn from the work of those who have come before us. And it’s reassuring to think that even as we make so much progress, some things never change, and I hope the struggle between nature and culture is one of them – they both have so much to teach us.

For more on the history of Lands End:

On Adolph Sutro: http://www.sfmuseum.org/sutro/bio.html

On Sutro Baths: http://sutrobaths.com/explorebaths.shtml

On the Cliff House: http://www.cliffhouseproject.com/introduction.htm

On Merrie Way: http://www.outsidelands.org/merrie-way.php

On the new Lands End Lookout: http://www.parksconservancy.org/park-improvements/current-projects/san-francisco/lands-end-lookout.html

Phoebe Schenker, AIA, LEED AP BD+C

Project Architect

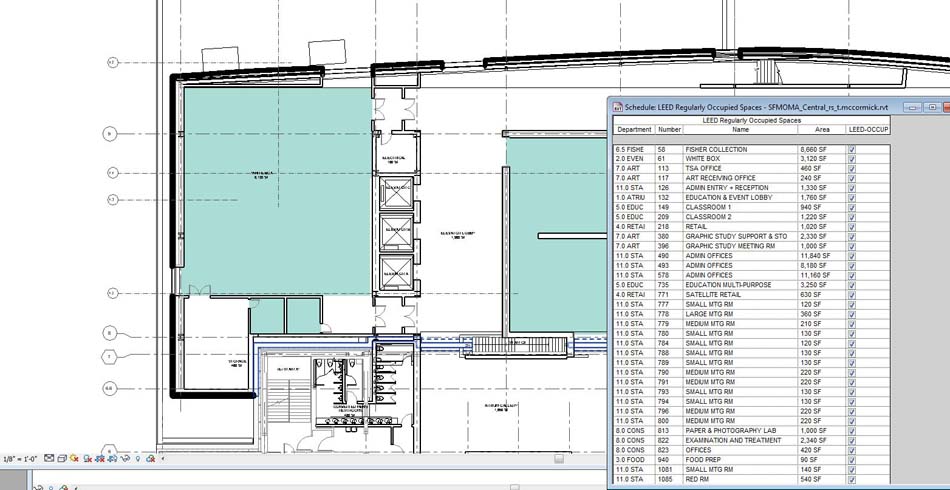

BIM at EHDD

BIM, the final frontier, or is it just the beginning?

When I arrived at EHDD years ago, the office had just started its first pilot project using BIM softwarecalled Autodesk Revit. When we first started BIM, our design teams often struggled with different aspects of the tool. At that point we seldom used the 3D model tool for design presentations, it waschallenging to achieve acceptable graphics for construction documents, and all of our 2D detailing still had to be done in conventional drafting software. Since then, the firm has grown substantially, and we use BIM on all projects and in all design phases. As I walk through the office today, I see Revit on every computer screen, digital models in almost every presentation, and teams using the tool in new and creative ways.

Our projects and clients have benefitted from BIM. Most clients today expect that a design team should be able to quickly show a 3D model of any portion of the building during the design phase. It is common place for us to use the same model to generate concept plans, massing diagrams, building area reports, rough quantity take offs, and to generate photo realistic images of the building design. Our clients often use our architectural design models during construction to coordinate different trades. Even though the models are not perfect, they do allow all of the stakeholders in the project to anticipate problems before the building is built. A contractor once confided in me that using BIM during construction is great because 90% of the problems are worked out before the installers arrive onsite.

Despite its benefits, implementing BIM has not been without challenges. From the very beginning, we have had to constantly manipulate the software to make graphic improvements to our drawings, we struggle to add accurate 2D and 3D content to the model at appropriate times, and we are spending an increasing amount of time making model corrections. We are generating our details from the model which allows us to connect directly to the 3D database, but not always with increased accuracy or coordination. The truth of the matter is that the AEC industry and project expectations are rapidly changing. Tight fees and schedules often lead to problems later down the road. In an ever changing world, we have to constantly sharpen our strategies of effectively communicating the design intent.

The next chapter of BIM development at EHDD will likely be focused on how to better leverage the data that is put into the model. Models in the future could be set up to render and animate unlimited views of the building, contain all equipment and building services parametrically linked, have countless schedules taken directly from the model that outline everything from how much concrete is on the project to what team member is working on what sheet. The possibilities are truly endless. Will we get there? We may need to sooner rather than later.

Terry McCormick, AIA, LEED® AP BD+C

Associate

Earth Day 2012

Looking back at early environmental movements prior to Earth Day 1970, we see many old ideas returning, particularly attitudes about community, localism, and reaction against globalization. In recent decades the green movement has grown up with the amazing developments in science and accompanied by the inevitable bureaucracies needed to foster change at the scale required by our environmental challenges. The result has been a focus on metrics and technical transformations within conventional market economies. In contrast, movements leading up to the first Earth Day were centered around philosophical and cultural transformations. I am referring to the utopian and ecological movements that started with John Muir, Ruskin and Thoreau, the Back to the Land movement, the hippie communal movement, and including anarcho-enviromentalism. Amidst the abundance of current green ideologies one can distill environmentalism into two general schools of thought: The technocratic and the communal. The technocratic espouses mainstream transformations through science, analytics and politics while communal refers to the older mode of grassroots, community and spiritual transformations. It’s E.O. Wilson’s Consilience versus Wendell Barry’s Life is a Miracle; establishment versus subversive; the spectrum between those that believe we will succeed in manipulating nature through science to those that believe there is something intrinsically good about humanity and unknowable in nature.

Current sustainability ideals have lost much of the rebelliousness epitomized in the pre Earth Day era by people like Aldo Leopold, The Farm, the Merry Pranksters, or the Nearings, who chose unconventional paths. There were also analogous revolutionary movements in design with Black Mountain College, Bucky Fuller’s “Spaceship Earth”, Drop City, Jane Jacobs, Arcosanti, and later on Christopher Alexander’s “Pattern Language” theories. These people approached environmental problems with artistic inputs and the deconstruction of societal norms.

The specter of catastrophe and intense focus on environmental metrics, bogged down in debate and politics, do not appear to be compelling enough to cause the transformations we need, and I wonder that if as a people we re-emphasized the older humanist ideals espoused by the communal movements: caring for one another, schooling our children, doing meaningful work and creating meaningful jobs, consuming less, and re-establishing age old patterns of stewardship. By rebuilding our commons, perhaps we would have less need to regulate in the first place.

Now we see many of the values of old returning: the value of real work, hand craft and “making”, experiential learning, collectivism, and the rejection of the political center.

People are taking back communities both rural and urban, forging neighborhood bonds, and taking responsibility for their own wellbeing. People are growing small businesses in unexpected places, developing local economies, creating goods that are unique and place specific. These can be healing and regenerative like the urban farms in Oakland and Detroit, civic and transformative like burgeoning bicycle infrastructure in many major cities, or cosmopolitan like the locavore crazes in San Francisco and Portland.

In the spirit of this humanistic revival EHDD has evolved. Our sustainability practice has generally focused on innovative building solutions and research. Now, our urban design studio allows us to foster environmental change at larger scales and in places, like India, where the need for thoughtful urbanism is most needed.

Sadly last year saw the close of the NASA Space Shuttle program, conceived around the time of the first Earth Day. One of the great successes of NASA’s recent space exploration is their Earth Science mission which is revealing the earth’s natural patterns, looking in instead of out. It is fitting that a NASA image of the earth from space came to symbolize the environmental movement. With our selection as executive architect for the California Science Center Air and Space Center – which will house the Space Shuttle Endeavour – EHDD will be at the table as the environmental movement enters its next phase.

Closer to home and channeling our inner localista we are creating tighter bonds within our community. We have hosted artful gatherings and are investigating the creation of a “parklet” near our office. We have volunteered at local food banks and are always looking for new outreach opportunities. We are also participating in the Climate Ride in September – a 350-mile bicycle ride to raise money for environmental organizations.

It is compelling to think that a good idea is a good idea no matter where it comes from and when it comes to sustainability more is better; that communal ideals benefit the technocratic and vice versa.

At EHDD we don’t just ride our bikes to work, we ride them across California! Happy Earth Day!

Andrew M. Sohn AIA LEED® AP BD+C

Senior Associate

What’s the value of architecture school?

The movie begins with ping pong and a chicken. More precisely, it begins with a group of architecture students finishing their final projects late at night—the chicken and ping pong arising naturally from the chaos. The film, follows a group of Indian architecture students in the 1970’s, and is based loosely on novelist Arundhati Roy’s own experiences. There are afros. There is colorful Indian slang. It is a window into another world.

And yet, it is unexpectedly but intensely familiar. My own architecture school experience did not take place in the 1970’s, and occurred on an entirely different continent, and yet is immediately recognizable. Intense conversations, check. Caffeine addiction, check. Petty rivalries, check. And of course, ping pong, check.

This of course, would just be an amusing exercise in reminiscences and shared cultural touchstones if it weren’t for unsettling real-world interjections into this collegiate atmosphere. In Georgetown University’s recent study on the employment trajectories of various typical undergraduate majors, architecture and arts yielded the highest unemployment rates among all college degrees.

More broadly, today’s political and economic environment is less than enamored of the classic liberal arts education, to which architectural education is closely philosophically tied. With an increasing emphasis on global competitiveness and performance, more practical educational programs (think: engineering, IT infrastructure, green technology, medicine) seem critical; philosophy and the arts, less so. Moreover, given the Georgetown study, these criticisms are not without some merit. After all, if you walk out of your final studio with $100,000 of debt and no job, an expertise at ping pong is scant comfort.

So, what is the value of architecture school? What do you get for the sleepless hours, the painful presentations, the impenetrable jargon? And more importantly, what do clients get that is valuable and unique?

Things you get (from architecture school):

Abundant practice in public speaking (even under conditions of stress and exhaustion)

Basic technical knowledge

Comfort with the latest technological tools

Cocktail party conversational starters—or enders—about famous architects

However, I think the most fundamental part of architectural education is less tangible. The studio system teaches students to take big ideas and to manifest them in concrete, particular, small(er) scale ways. The student takes a Big Question—the future of education, the experience of a city, income inequality, social justice—and attempts to respond using what is, overall, a fairly limited toolkit of material and geometry. Inversely, successful projects (and successful architecture) operate at both scales: a well designed building/city/detail can suggest something larger and intangible about the world around it. This is a difficult and thorny process: hence all the late nights, and frustrating critiques.

However, this skill is valuable. In fact, this sort of large-scale/small-scale thinking is becoming more and more common at the top-ranked business schools—Harvard, University of Chicago, UC Berkeley. And yet, business school graduates less frequently come away with only debt and ping pong. If this type of thinking is a fundamental part of architectural education, and is otherwise clearly valued in the current economic market, why are architectural job prospects and financial compensation so distinctly dim?

In part, due to what you DON’T get (from architecture school):

Business training of any sort

Outside opinions

Architecture schools are highly insular—they are regulated by NCARB, and their faculty is largely made up of other architects and planners. This means, that though teaching critical thinking and design strategies with universal value, most studios consider projects unsuccessful if it’s not, in the end, a building/landscape/city/installation. This does a disservice to the incredible creativity that thrives within architecture schools—and it does a disservice to the profession that these schools serve. It’s too bad that the innovation generating new façade languages cannot also be used to generate new approaches to real estate development, or different ways to articulate planning directives, or even new business models for architectural practices. Architecture schools should recognize the broader value of their existing pedagogy; ultimately, both architectural practice and education will be stronger.

The craft entrepreneur may provide lessons for architects. As recently discussed in the NY Times, the makers of artisanal pickles and gourmet beer are boosting the new American economy. These businesses work economically by sidestepping the trap of cheapness. Most notably, they offer creativity and quality – two things that an architectural education prepares us to offer – so people pay more for their products. By articulating the value of our own education, we position ourselves to better articulate the value of our profession.

Leah Marthinsen, LEED AP BD+C

Designer

A Mumbai Master Plan

I recently returned from a trip to India, as a part of an EHDD team lead by Michel St. Pierre (principal and director of urban design) along with Jennifer Devlin (EHDD India managing principal) and Dave Vogel, (associate principal). We were there to take part in an intensive, four-day design workshop with our client, a Mumbai-based developer who commissioned EHDD to create a new masterplan for a 24-acre site in a northern suburb of the city.

An initial masterplan was completed in 2009 with a mixed-use program that included four million square feet of housing, retail, office, and cultural uses. Recently, after construction on the first phase had begun, local authorities upzoned the area to incentivize greater development density in close proximity to a planned transit corridor and new station. Aiming to capitalize on the increased allowable density the client commissioned EHDD to redesign the original master plan to accommodate the increased development program, up to seven million square feet total.

In the weeks leading up to the trip, EHDD’s design team worked tirelessly to devise several alternative schemes to meet the twin challenges of maintaining a sustainable and livable environment within the increased density, and working with the buildings and infrastructure already underway on site. The team produced 40+ full size color presentation boards describing and diagramming a myriad of options and alternatives for the site, enough to cover every wall of the conference room.

The EHDD and client teams were joined by a host of stakeholders, consultants and specialists, including local architects who provided the needed interpretation of the complicated planning codes in Mumbai; traffic engineers to strategize for the flow of thousands of cars through the site and onto nearby roadways; and sustainability experts to advise on the wide array of site development and green building features in the project and optimize them for the unique Mumbai climate.

After four straight days of lively debate, flurries of sketching and on-the-fly computer modeling, a new scheme emerged which addressed all of the competing factors of the large and complex project, while offering the flexibility for several future-phase variations. In the end, the preferred solution was a synthesis of many options developed during the workshop that incorporated all the critical issues discussed with the entire group. The EHDD team returned to San Francisco with a clear design direction, and we are now developing the overall design into a concept master plan that will form the basis for the overall development of the project for the years to come.

Joseph Schollmeyer

Designer, LEED® AP

Challenges in Creating Sustainable Cities

A recent article in The New York Times entitled “Across Europe, Irking Drivers Is Urban Policy” raises some fundamental issues about how to create truly livable and sustainable cities. Several European cities are tackling the issue of car management full force, resisting the notion that a city needs to accommodate cars to remain commercially viable. The model that has characterized how North American cities have developed since World War ll has greatly emphasized the vehicle. It is inconceivable that such a model can prevail today, knowing its tremendous impact on the environment and given the sophisticated public discourse about what makes a great place to live and work. Nonetheless, when we are designing commercial and mixed use developments in many California communities, we are often required to meet parking standards that are not in sync with the public discourse. In fact, by mandating a high minimum parking requirement (rather than a maximum), municipalities are providing a de facto incentive for citizens to drive a private vehicle as a means of commuting. This is especially relevant today in light of new California state laws that require cities to address climate change. It is well known that, in most municipalities, the largest factor in green gas emissions (CO2) is private car usage.

Parking ratios determination is probably one of the most misunderstood aspects of planning. Parking requirements mandated by a given municipality are often based on precedents from other municipalities. Most of the time the underlying assumptions used in the original parking requirements are unknown to most, and thus difficult to challenge. It is critical to conduct a site specific study assessing all potential modes of transportation and potential carpooling to determine what is the appropriate amount of parking needed. Incentives towards promoting sustainable forms of transportation should be a key element of any planning regulation.

Cities like London and Montreal have taken bold step towards making cycling a true alternative form of commuting. In some areas of London, cyclists overtake rush hour drivers and dictate the speed of traffic. Montreal developed an extensive network of safe and segregated bicycle lanes throughout the city, not dissimilar to those in Holland and Denmark. The program has proven to be so popular that the city now faces a serious cycling congestion problem during rush hours, which leads many bike riders to veer off the path and take their chances amidst the automobiles.

There is a clear need to put greater emphasis on infrastructure for bike mobility and storage. Once that infrastructure is in place, we can make our cities drastically more healthy and livable, while considerably reducing our carbon footprint.

Michel St. Pierre

Director, Planning and Urban Design Studio

Let there be “Light”

Situated next to Valparaiso University’s monumental Christopher Center for Library & Information Resources (EHDD project built in 2004), the smaller, recently completed College of Arts & Sciences Building longed for a presence to stand its ground. The modest addition does not architecturally upstage its brawnier older sibling, even though the two buildings share entrance frontage and a physical connection. Instead the new architecture graciously respects the signature massing of the Christopher Center by using clean volumes and similar materials. Where it shines, though, is through its veil.

That veil, which hangs above the building’s entryway, is a tapestry of words that are waterjet cut out of aluminum plate. The words form a half-inch thick screen covering a portion of the second story façade. The screen spans thirty feet in width and rises the full height of the window wall above the building’s front doors. It is painted light gray so that during the day its color matches that of the mullions and trim. At night it becomes silhouetted by the interior light of the Faculty Commons Room behind.

Designing an entrance veil was not intentional. The screen was an inadvertent result of a solar mitigation study for the opposite side of the building. An earlier design scheme proposed a sizeable exterior sunshading system to wrap the building’s southern exposure. That screen was ultimately value-engineered out of the project, but its concept (a pattern produced by tessellating the letters V-U) left a bright impression. The desire for a design element that acknowledged the inhabitants of the College of Arts & Sciences Building remained.

After iterations of various graphic patterns passed over the drawing board, focus landed on the University’s Latin motto: In luce tua videmus lucem. Translated into English this reads: In thy light, we see light. The Foreign Languages Department, tenants of the new building, warmly embraced a tapestry of words based on the Latin phrase. The screen is an amalgamation of translations for the word “light” in thirty languages which represent the home countries of every student on campus. The nine languages taught in the building are shown larger, while the remaining translations help to compose a field condition. At the center of the screen lies the Latin motto itself.

The screen survived its way through project cost cuts because the building’s users bought off on the concept early on. That is not to say its construction dodged technical challenges; it did not. Nevertheless, all parties remained fervent in their efforts to execute the original idea. Now installed, the screen graphic has started appearing elsewhere around campus: on admissions brochures, Family Weekend coloring books, and even t-shirts. The building’s identity is now known.

Matt Soisson

Designer, LEED® AP

The Audacity of Architect Barbie

March 3, 2011

By Jessica Lane, AIA, LEED AP® BD+C

The recession has hit architecture firms hard. There is the sense that Americans have cast their vote for worthwhile investments to ensure a better future, and buildings have not made the list. It is easy to lose hope amidst all of this, but there is reason to believe that architecture still holds an important place in the American psyche, a symbol of ambition, fortitude, integrity, keen discernment, taste and tact, the staunch and resolute:

America, meet Architect Barbie. That’s Ms. Barbie, AIA, to you.

Mattel will offer the doll as part of the “I Can Be…” series, which features Barbie in various professional or vocational roles; several options are announced, and the public is asked to weigh in on the best career choice. Architect Barbie has been a repeat competitor over the years, but like a good project put on hold, it just never panned out. Considering winners of years past — Dolphin Trainer Barbie and Actress Barbie come to mind — one notes that America tends to direct Barbie toward careers that are exciting and glamorous, if not intellectual. Tellingly, Architect Barbie did not actually win the popular vote — Mattel chose her anyway.

While we’re flattered, we’re also, well, maybe a little perplexed. Is Barbie ready, we worry, to settle down at a desk and pore over wall sections? More to the point, what happens when the hard hat ruins the hairstyle? Is the client going to listen to Hat-Head Barbie? AIA’s Young Architect Prize-winners, attending to these concerns with vigor worthy of an eleventh-hour redesign, have suggested such improvements as cutting her hair short, ditching the skirt in favor of site-visit-friendly pants, and carrying a laptop computer in place of the blueprint tube (seriously, no way would Barbie be so behind the times!).

Sure, that’s one way to look at it. But that sort of drastic redesign also seems like a Value-Engineering list that threatens to eviscerate a project. I submit that Architect Barbie is onto something.

If Mattel has perfected the art of taking the pulse of American visions of their children’s futures, with Barbie as the particular litmus test of our ideals of women, I suddenly feel a lot better about architecture’s prospects. For one thing, Architect Barbie, as many critics note with disdain, is unapologetic about her incongruous and un-architect-ey appearance — from the dearth of black clothing to the unmistakable platinum ponytail. The crisis (if you’ll allow liberal cribbing from “Legally Blonde”) is not that Barbie doesn’t look like a “real” architect, but that without the blueprints and the black, we’re perhaps not sure what an architect does look like. The culture as a whole (viz. the musician Girl Talk and open-source software) is skewing toward appropriation and hybridity, and away from the identity and ownership as being fixed and discrete. In fact, with her shameless black-glasses-and-purple-dress mash-up, Barbie joins the ranks of Michelle Obama and Kirsten Gillibrand, who prove that style-consciousness and career success are no longer mutually exclusive for women. Forget the pilly black turtleneck and furrowed brow of architect icons past; Barbie suggests that women infiltrate male-dominated professions by bringing our own personality and unique talent to bear. Indeed, other recent “I Can Be…” winners, Computer Engineer Barbie and News Anchor Barbie, nod to the uniforms and accoutrement of their professions without taking them literally: News Anchor actually looks like she took the stiff Anchorman suit and handed it to the House of Chanel for revamping.

As for Architect Barbie as a believable purveyor of aesthetics and design, a preference for plastic and vinyl (pink or otherwise) puts her squarely in company with cutting-edge practitioners like Jeanne Gang and Kazuyo Sejima (SANAA), who combine unusual materials with subtlety and playfulness. If Architect Barbie can be forgiven the admittedly bad outfit (unless the skyline depicted on her dress is meant to be ironic), the audacity of the ultra-feminine icon as an architect is actually pretty inspiring. It points to the certainty that if Barbie’s hair was shorn, heels traded for sensible shoes, dress for khakis, the doll would gather dust on the toy store shelf, too ordinary and whittled-away. She’s much more charismatic as she is — unafraid of ridicule, goofy grin and all.

What is so obvious to children is something we should remember: roles are for playing.

One certainty is that, once purchased, Architect Barbie will irreverently lose the document tube, don pieces of other costumes, and inspire adventures far more varied and complex than any representational outfit could possibly suggest. That, to me, sounds like “I can be what I want to be.”

Putting aside the endless criticism of Barbie’s (and let’s not forget that Barbie stands in for women architects) clothing and accessories, the more serious concern, of course, is the doll’s own unrealistic measurements, for which Mattel has weathered (and ignored) endless criticism. How does a doll with totally ridiculous proportions represent a profession that uses the human body as its base metric? Again, this is lost on kids (who would probably argue back that SpongeBob Squarepants’ total failure to faithfully represent sponges and toast doesn’t bother them all that much). We’re taking it too literally. When was the last time you met someone shaped like the Modulor?

The true debate is reflexive: Mattel’s choice of Architect Barbie says much more about adults’ wishes for their girls’ futures than it does about girls’ own ideas. We can count on the girls to invent their own stories; the fact that Mattel sees the doll as marketable means that battle has, effectively, already been won.

For architects, perhaps the dubious honor of our own Architect Barbie is best seen in that light: a vote of confidence from the collective unconscious of America. To architects’ inevitable protest that Barbie is seriously un-cool, that the whole getup is irredeemably cheesy, a familiar admonition can be heard: don’t be such snobs!

With the AIA noting that women constitute only 17% of their membership, even as nearly 50% of architecture students are women, maybe some audacious re-design is called for. Just hand me that pink laptop, and I’ll get on it.

EHDD’s Response to the “World Architecture Survey”

Vanity Fair recently polled leading critics, deans of architecture schools, and architects with two questions: what are the five most important buildings, bridges, or monuments constructed since 1980, and what is the greatest work of architecture thus far in the 21st century? The results highlight a glossy cannon of international starchitects and their iconic works yet no green buildings made the cut, spawning a flurry of response from the green building community. To add further fuel to the fire, architectural correspondent Matt Tyrnauer quipped in an interview with NPR that green buildings are just not sexy – at least not yet. Determined to counter this assumption, Lance Hosey from Architect Magazine surveyed green building professionals to build a ‘G-List’ of the best green buildings. The projects that made the list represent a broad range of interpretations as to what makes a ‘green’ building and many fall into the same trap that the Vanity Fair list does, focusing on aesthetics over performance.

The surveys and the torrent of discussion they generated demonstrate a deep divide within the architectural community in terms of what sustainability should mean for design. Can high design also be environmentally responsible? Can a green building represent the best of both architecture and sustainability? I would argue yes; however, to do so, architects must stop seeing sustainability issues as separate from design. Environmental responsibility must be integrated within the design process so that there is no longer a division between what qualifies as a ‘green’ building or as great architecture: it is simply one and the same. Buildings are silent partners in the future sustainability of the planet but architects have the unique opportunity to affect real change and to lead the charge for a more beautiful and environmentally sustaining future. We are creative problem solvers by nature; shouldn’t this be the most exciting design challenge of our profession?

To paraphrase Dr. Ray Cole, “buildings themselves are not sustainable; however, buildings can be designed to support sustainable patterns of living.” At EHDD, we are beginning to think beyond the building, recognizing that the process of designing beautiful and inspiring green buildings can be a catalyst for organizational change. The recently completed Learning Resources Center at Marin Country Day School does just that. The project has all the features and more of a high achieving LEED Platinum school: rainwater harvesting for cooling and toilet flushing; photovoltaics that produce 100% of the facility’s net annual energy needs; effective daylighting and lighting controls; native landscaping and stream restoration; and locally sourced materials with high recycled content. But it is more than the sum of these parts. The students, teachers, and parents all love the new buildings. The excitement generated by the project has galvanized the community in support of the school’s sustainability goals and these have been integrated into the curriculum as well as the campus master plan. Faculty report that they teach differently in their new daylit classrooms: the openness and transparency of the spaces encourages collaboration and engagement that wasn’t possible in their old rooms. Students are more relaxed and attentive as well. One student quipped that ‘other schools have hallways; we have trees for hallways.’ In essence, the architecture at MCDS inspires and right now we are in desperate need of inspiration; not from “sexy” energy hogs of buildings but from projects that celebrate architecture as well as sustainability and performance. Where’s the list for that?

– Janika McFeeley, LEED AP BD+C

Designer