Blog Archives

Educator Workforce Housing: A Blueprint for What’s Next

In California, teachers earn only 76 cents for every dollar earned by similar non-teaching professionals*—an enduring 24% pay gap—even as they try to secure housing in the nation’s most expensive markets. The result is sobering: many individuals live with roommates well into midlife, commute for hours each day, or relocate far from the communities they serve. This isn’t just a housing crisis—it’s an education crisis, directly impacting retention, recruitment, and the stability of California’s schools.

The roots of this crisis lie at the intersection of two forces: California’s severe housing affordability challenges and the systemic undervaluing of educator income. Both certified classroom teachers and classified staff, arguably our most essential public employees, struggle to secure quality housing near their schools. Without intervention, the gap between where educators work and where they can afford to live will only widen.

From Firsts to a Model: Santa Cruz Educator Housing

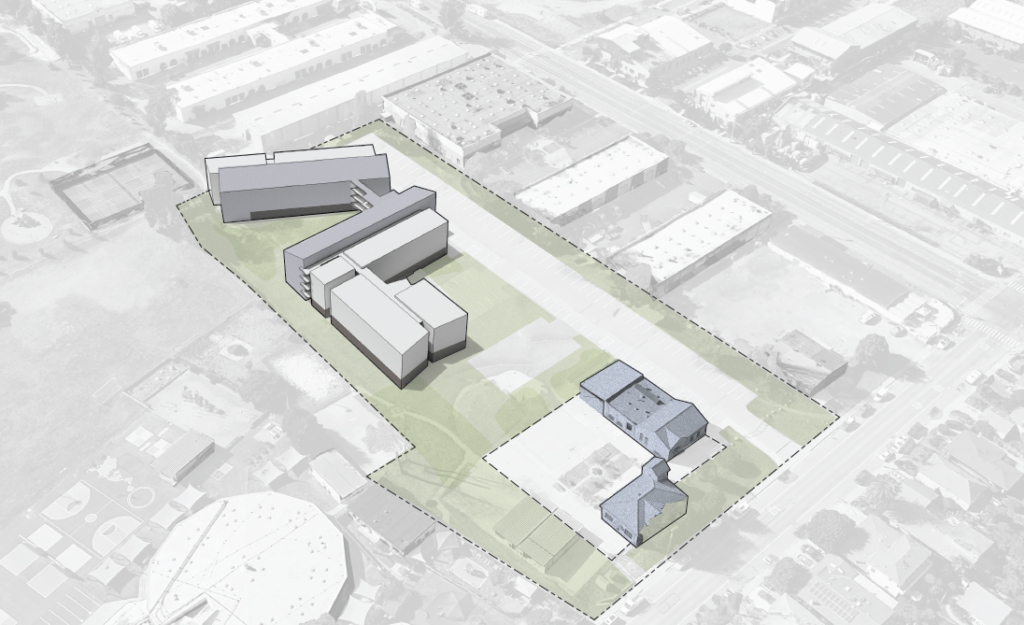

Santa Cruz City Schools is advancing one of California’s earliest educator housing projects — and EHDD’s first in this emerging building type — in a collaborative design-build partnership with Bogard Construction and associate architects Studio VARA.

The 100-unit community for SCCS K–12 teachers and staff includes studios, one-, two-, and three-bedroom apartments, and is among the first of its kind in California. As construction approaches, the project team is reflecting on lessons learned and sees Santa Cruz as an invaluable model for future workforce housing developments.

Policy Shifts Unlock Possibility

Over the past decade, California has led the nation in advancing legislation to promote workforce housing for educators. The Teacher Housing Act (SB 1413, 2016) first opened legal pathways for school districts to establish and fund housing for their staff, and for the first time allowed educator-only tenant pools. Building on that foundation, the Educator Workforce Housing Law (AB 2295, 2022) streamlined entitlements by deeming educator rental developments an allowable use on district-owned property, regardless of existing zoning or general plan designations, provided that a portion of the units are deed-restricted as affordable. These laws also enabled districts to dedicate surplus land to housing, transforming underutilized parcels into opportunities for staff to live near the schools they serve.

Alongside these policy shifts, counties, municipalities, and school districts have passed dozens of bond measures earmarking funds for educator housing. The momentum is clear: districts now have both the mandate and the means to act.

In Santa Cruz, EHDD worked closely with the school district to navigate this policy and funding landscape — aligning deed restrictions, zoning pathways, and local bond funding (Measures K & L). Through this process, we identified an opportunity to increase the project from 80 to 100 units, a move that both maximized the number of educators housed and improved efficiency of scale for the district’s investment.

Dozens of bond measures across California have earmarked funds for educator housing — momentum that districts cannot afford to ignore.

The momentum isn’t limited to California — the Pacific Northwest is also advancing bold policy measures to address workforce housing.

policy shifts in the pacific northwest

Across the Pacific Northwest, similar momentum is underway. Recent legislative actions in King County, Seattle, and surrounding municipalities are setting the stage for a new wave of affordable workforce housing. Seattle’s City Council recently approved Nelson’s workforce housing bill, while King County advanced a $1 billion bond study to expand access to social and workforce housing. Together, these initiatives echo California’s progress and highlight the growing urgency of providing affordable housing for the people who keep our communities running.

With active work in Seattle and the broader region, EHDD is committed to carrying these lessons forward — helping districts and municipalities address housing challenges for educators and other essential workers across the PNW.

Insights from Educators

Engagement with Santa Cruz educators was a defining part of our early design process. Teachers and staff spoke candidly about the toll of long commutes, cramped living situations, and the risk of leaving the profession altogether. During weeknight workshops on programming, amenities, and even materiality, we heard a diverse set of perspectives. Yet one message rose above all: we need housing now.

That urgency, paired with thoughtful input on unit sizes, amenities, and common areas, directly informed the project’s design from its earliest stages. The result is housing shaped not just for educators, but with them.

Educators told us clearly: we need housing now.

Designing for Privacy and Community

Educator workforce housing is a unique building type. Unlike typical affordable housing, all residents here work for the same organization — sharing schedules, workplaces, and coworkers. This reality shaped our design approach from the start: how do we create a sense of individuality while supporting connection among colleagues?

We emphasized differentiation of units and organized the building into smaller “neighborhoods” across three distinct masses, allowing each resident to feel a sense of private domain. At the same time, we leveraged the project’s exterior circulation — widening upper-level bridges and walkways to capture ocean views — and layered in a variety of outdoor spaces to support common use and gathering without adding excessive conditioned space. The balance is intentional: private respite paired with meaningful community “nodes.”

Designing educator housing also requires creativity with site constraints. Most projects will be built on district- or city-owned parcels not originally intended for housing. Often these parcels are unusually expansive or oddly constrained sites, meaning each project requires bespoke analysis rather than a one-size-fits-all template. In Santa Cruz, we shaped efficient double-loaded residential wings into four-story bars, connected by elevated bridges and exterior walkways. The result is an architecture of housing-in-the-park: relatively dense massing thoughtfully composed in the landscape to shape a series of outdoor spaces of varying scale and orientation. It is a gracious but cost-effective delivery of compact residential units within a fabric of lush, human-scale shared spaces.

Educator housing demands design that balances privacy with community — compact, efficient, yet deeply human.

Educator Housing Is Just the Beginning

Educators everywhere deserve thoughtfully designed housing, and every district deserves teachers who can live and thrive in their local communities. As a new development type, educator housing offers architects, builders, and developers an extraordinary opportunity to strengthen communities.

For EHDD, with eight decades of experience in both housing and education design, this is a natural — and essential — evolution of our practice. Workforce housing is not just about buildings. It is about ensuring that the people who make our communities thrive — teachers, nurses, municipal staff, and beyond — can afford to live where they work.

We see workforce housing not just as a building type, but as a civic responsibility.

Educator housing is at the forefront of a larger movement. Nurses, city staff, and first responders — all deserve the chance to live in the communities they serve. EHDD’s commitment is to design workforce housing that not only addresses affordability but also strengthens connection, dignity, and belonging for the people who keep California’s communities thriving.

¹ Center for Economic and Policy Research, California Teachers’ Wage Gap Getting Wider, Jan 2025. Link to Article Here

This piece was developed in collaboration with Zachary Gong, AIA, Architect and Associate at EHDD. Zachary leads workforce housing and education design projects, including the Santa Cruz City Schools educator housing community, scheduled to break ground in 2025.

About EHDD

EHDD is an award-winning architecture firm with a strong commitment to advancing climate action through sustainable design. With decades of experience helping clients achieve their dreams, EHDD creates transformative places of belonging and impact. Learn more at ehdd.com

Media Contact

Ana Wansink

Director of Marketing & Business Development

EHDD

a.wansink@ehdd.com

+1 (415) 214 7271

EHDD Announces the Passing of Founding Partner Charles “Chuck” Davis, FAIA

May 14, 2025

Architect of place, purpose, and possibility.

San Francisco, CA — EHDD shares with profound sadness the passing of Charles “Chuck” Medley Davis, FAIA, the last surviving founding partner of the firm. The youngest of EHDD’s four original partners, Chuck was instrumental in establishing EHDD as a nationally respected practice, defined by collaboration, sensitivity to place, and a mission-driven approach to public architecture.

Chuck was known for his warmth, humility, and insight and brought a distinctive combination of rigor and care to every project. He prioritized client needs, place-based solutions, and long-term resilience over authorship or formal signature.

EHDD has long been defined by a collaborative design culture—a hallmark of Joe Esherick’s approach from the firm’s earliest days. Chuck was one of its most dedicated exemplars, cultivating a studio deeply committed to mentorship and hands-on learning—what many would come to regard as one of the Bay Region’s great teaching offices. His focus on solving real problems rather than imposing preconceived ideas became one of the firm’s enduring values.

Chuck’s design legacy spans some of EHDD’s most impactful work. Alongside the Monterey Bay Aquarium and numerous other public institutions, Chuck contributed to projects across all ten University of California campuses, the Exploratorium, and aquariums around the world—including in Chicago, Taiwan, Long Beach, and beyond. His buildings have welcomed millions of people, and his collaborative ethic—his belief that we could always do better—left its mark on every partner, consultant, and team he worked with.

Chuck believed that “successful teaming and fighting like hell to do what was proper for the client” mattered more than design ideology. His work was marked by patience, generosity, and an unwavering belief in the architect’s duty to serve the public good.

Jennifer Devlin-Herbert, CEO of EHDD, reflected on Chuck’s collaborative ethos:

“What I learned from him is that you build from what people are doing. You influence it and bring wisdom to it rather than being the author… The idea of a single author is badly outmoded.”

Chuck was a cultivator of people—his quiet guidance helped shape the DNA of EHDD. He inspired generations of architects through his open-door leadership, deep curiosity, and enduring belief in the power of design to do good. A big man with a big personality, Chuck will be remembered for his booming laugh and infectious sense of humor.

“Chuck was the best at making the architects know that he was there for them,” recalled former EHDD colleague Mary Collins. “He walked the floor. He didn’t just sit in his office—he was out there, and he invited people in.”

Chuck was larger than life—physically, emotionally, and intellectually. Fierce in his convictions and generous in his counsel, he made time for everyone, no matter how long he’d known them. He lived with purpose and stayed engaged with EHDD, the profession, and UC Berkeley well into his final years—always calling, always checking in, always believing in the work and the people doing it.

EHDD will be honoring Chuck’s life and legacy in the coming months through a public tribute series and shared remembrances from across the firm and the broader design community. Friends, collaborators, and former colleagues are invited to participate and help celebrate a remarkable life in architecture.

About EHDD

EHDD is a nationally recognized architecture and design firm based in San Francisco, known for shaping transformative spaces that serve the public good. Founded in the 1940s by Joseph Esherick and later formalized as Esherick Homsey Dodge & Davis, EHDD has built a legacy of design excellence in education, science, culture, and civic life.

Rooted in the belief that architecture should reflect purpose, context, and community, EHDD approaches every project with a collaborative spirit and a deep commitment to environmental responsibility. The firm has long been a pioneer in sustainable design and climate leadership, helping clients across the West Coast and beyond achieve ambitious goals through thoughtful, future-ready architecture.

With a portfolio that spans iconic institutions—from the Monterey Bay Aquarium to award-winning university campuses and cultural buildings —EHDD continues to create places of belonging and impact. Learn more at ehdd.com

Media Contact

Ana Wansink

Senior Marketing & Communications Manager

EHDD

a.wansink@ehdd.com

+1 (415) 214 7271

Climate Tech Pioneer C.Scale Emerges from EHDD to Advance Building Decarbonization with Accessible and Actionable Carbon Data

November 12, 2024

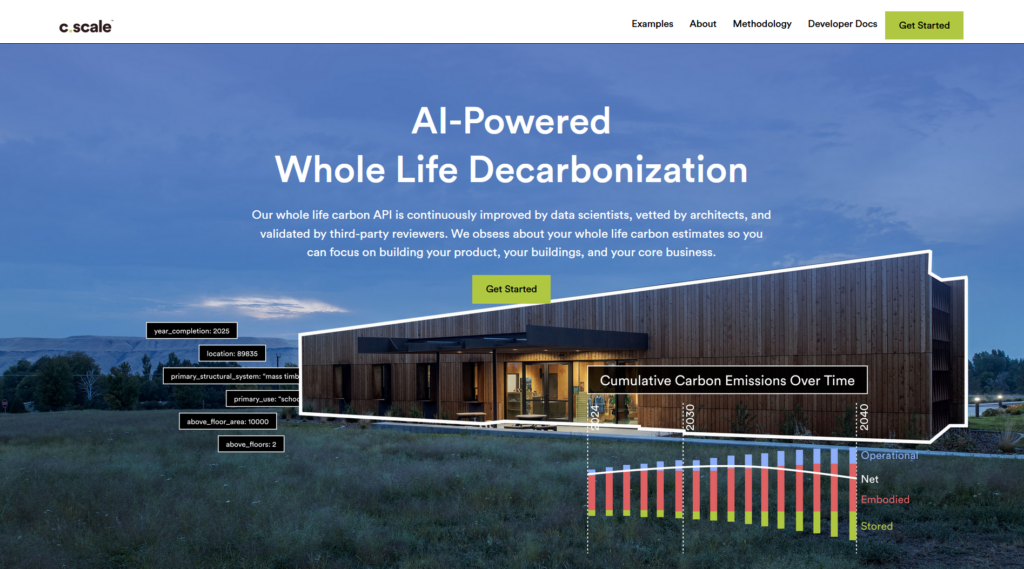

EHDD, a national leader in sustainable architecture, today launched C.Scale as an independent public benefit corporation poised to revolutionize the building industry’s approach to decarbonization.

SAN FRANCISCO, CA – EHDD, a national leader in sustainable architecture, today launched C.Scale as an independent public benefit corporation poised to revolutionize the building industry’s approach to decarbonization. This strategic spinoff unleashes groundbreaking machine learning technology that promises to transform how the architecture and construction industries tackle climate change.

C.Scale’s breakthrough platform democratizes access to critical carbon data and decision-making tools, enabling any building project – from small renovations to large-scale developments – to achieve ambitious decarbonization goals. The company’s proprietary machine learning models solve fundamental data problems in the AEC industry, delivering comprehensive carbon insights from initial concept through final construction at a fraction of the cost of existing solutions.

“The climate crisis demands bold action at unprecedented speed and scale,” said Jack Rusk, CEO and Co-Founder of C.Scale. “As an independent company, C.Scale can now accelerate the deployment of our technology to transform how every building project worldwide approaches carbon reduction.”

Rusk, former Director of Climate Strategy at EHDD, is joined by Co-Founder Brad Jacobson, FAIA, whose 22-year track record of delivering net-zero projects at EHDD brings unparalleled industry expertise to the venture. The spinout recognizes that building successful software requires a different business model than professional services, positioning C.Scale to attract the investment needed to fulfill its vision.

Built on EHDD’s track record of climate leadership, C.Scale has already made a significant impact in the market. Its EPIC tool, released as an open-access platform in 2022, has become a cornerstone for low-carbon building design with over 5,000 users worldwide. Major players across the building industry ecosystem – from software giant Autodesk to global engineering leader Schneider Electric and architectural innovator Foster + Partners – have integrated C.Scale’s API into their own tools, validating its potential to become an industry standard for building carbon analysis. This spinoff positions C.Scale to launch an expanded platform that will support the entire building lifecycle, from early-phase carbon estimation through compliance reporting and construction.

“This spinoff demonstrates the power of combining architectural expertise with cutting-edge technology and will allow this initiative to flower on its own” said EHDD CEO Jennifer Devlin-Herbert. “C.Scale is a success story of how innovation within architecture firms can catalyze industry-wide transformation. We’re proud to have incubated a solution that will accelerate our profession’s response to climate change.”

About EHDD

EHDD is an award-winning west-coast architecture firm with a strong commitment to advancing climate action through sustainable design. With decades of experience helping clients achieve their dreams, EHDD creates transformative places of belonging and impact. https://ehdd.com/

About C.Scale

C.Scale is predictive software enabling zero carbon buildings. Its mission is to enable the full decarbonization of the built environment through democratizing access to climate strategy for designers and owners of all buildings everywhere. https://www.cscale.io/

For more information, contact Ana Wansink: a.wansink@ehdd.com

EHDD Awarded Two New Waterfront Commissions in Puget Sound

EHDD has been commissioned to design a new commercial waterfront center at the Port of Olympia and a series of projects through an IDIQ with the Port of Seattle

Seattle, WA – EHDD is proud to announce two new commissions that strengthen our role in shaping the future of Puget Sound’s shoreline. The first, a new waterfront center for the Port of Olympia, and the second, an IDIQ contract with the Port of Seattle, reflect EHDD’s ongoing commitment to delivering resilient, sustainable design solutions to the Pacific Northwest.

“These commissions mark another milestone in EHDD’s legacy of impactful waterfront design, helping to redefine the region’s coastline for future generations,” said Christopher Patano, EHDD Principal who leads EHDD’s Seattle office.

A New Waterfront Center for the Port of Olympia

EHDD was selected to design a new waterfront Center for the Port of Olympia at their Swantown Marina site along Budd Inlet. EHDD and the Port of Olympia will work together to program a new facility while aligning the waterfront center with an overall port peninsula integrated master plan and 2050 vision for the Port of Olympia. The new waterfront center will be a catalyst for connecting the port’s facilities to community favorite amenities like the Farmers Market, Hands on Children’s Museum, and Percival Landing.

A market analysis is expected to begin in late 2024 with the overall process leading to expected design work in 2025 and anticipated construction beginning in 2027. The waterfront center will have opportunities to highlight locally sourced wood products, enhancing the legacy of the timber industry in Olympia while providing a low-carbon structure that sets a new standard for sustainability and energy efficiency. EHDD’s waterfront team includes Groundswell, StructureCraft, Mazzetti, Moffatt & Nichol, Haley & Aldrich, Cushman & Wakefield, and Blanca lighting design.

Five years of design for the Port of Seattle

We’ve been working with the Port of Seattle since 2007. EHDD has been selected by the Port of Seattle for a five-year IDIQ Buildings and Structures contract, and our Seattle office will be supporting the port’s efforts to increase value and utilization of the port’s properties.

The waterfront work requires a complex team of architects and consultants, EHDD’s team includes Mazzetti, Moffatt & Nichol, Haley & Aldrich, KPFF, Integrated Design Engineers, Strata architects, and Blanca lighting design.

Both projects leverage EHDD’s deep waterfront expertise, integrating locally sourced materials with carbon-positive strategies to create environmentally responsible, durable, and beautiful spaces. Our team draws on decades of experience collaborating with regulatory agencies to ensure that each project aligns with both community goals and environmental best practices.

About EHDD

Founded in 1946, EHDD is a West Coast architecture firm with offices in San Francisco and Seattle. The firm is credited with pioneering the net zero energy building concept more than 20 years ago. Today, they are leading the way through built projects and applied research to collaboratively decarbonize our built environment. With a mission to create transformative places of belonging and impact, EHDD works with a range of clients with a focus on arts and education non-profits, visitor-serving institutions including aquariums and parks, and leading-edge corporations dedicated to leadership in sustainability and social impact.

Art & Architecture: Designing the Frit Pattern Façade for the Iconic AIA Headquarters

Before becoming a graphics specialist in architecture, I honed an art practice that reimagined place through sound, visuals, and installations. I was trained in drawing, painting, and printmaking methods, alongside a range of digital technologies, which provided a creative foundation that, today, shapes my practice at EHDD in profound ways.

Some of these influences are evident, such as my design of the feature art wall for UC San Diego’s Design and Innovation Building where I integrated the artwork into the lobby’s architecture. But there are subtler, yet equally powerful ways that artful design enhances the experience of a space.

Recently, I had the opportunity to draw from my printmaking background while designing a custom frit pattern for the façade of the American Institute of Architects headquarters building in Washington, D.C. By blending my artistic approach with advanced digital tools, I helped craft a façade that is both high-performing and deeply experiential.

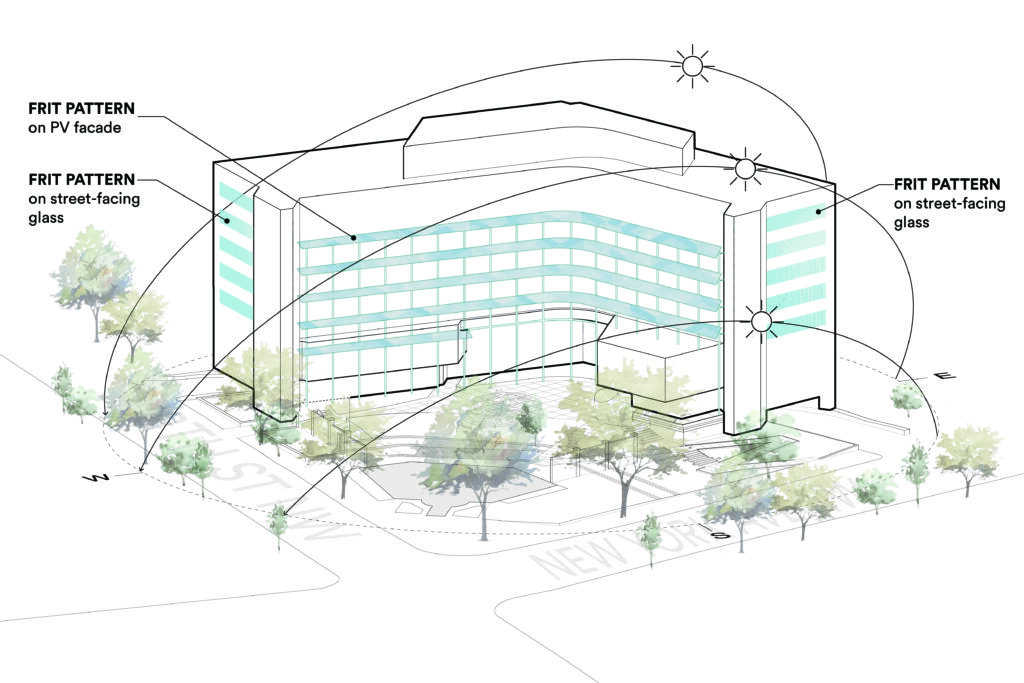

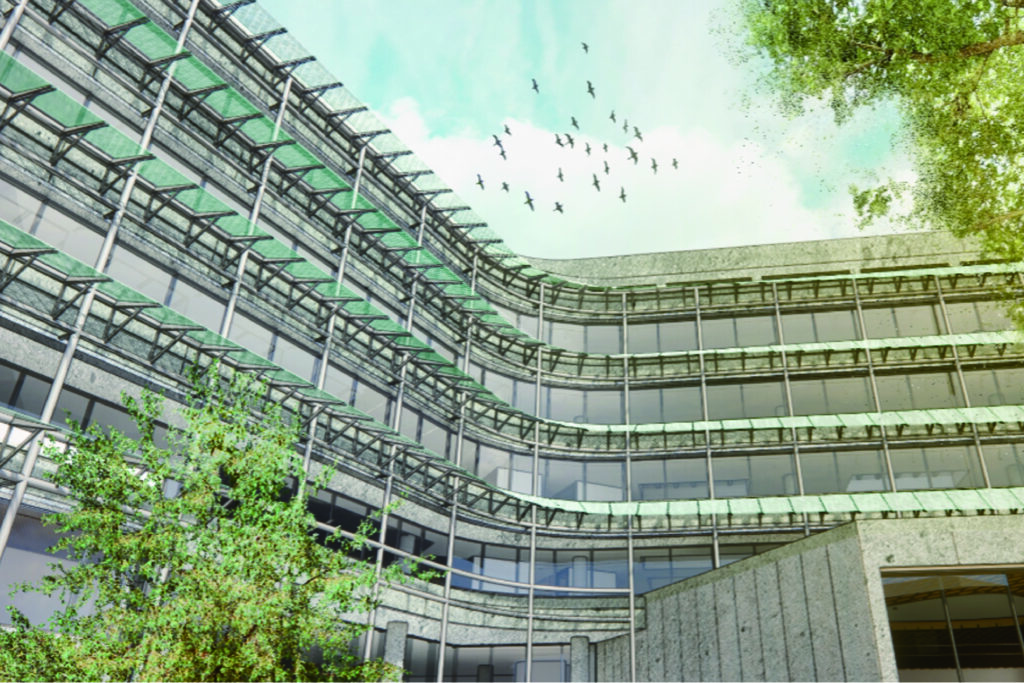

At EHDD, we’re renovating the AIA headquarters, an iconic 1973 Brutalist structure, to align with the AIA’s values, both in terms of performance and design aesthetic. Our goal is to transform the United States’ home for architects into a beacon of sustainability, meeting the AIA 2030 Commitment by decarbonizing the building, fully electrifying its systems, and harnessing renewable energy. Equally important is the renewed human experience of the space, creating a high performing, biophilic environment that enhances wellness for employees, members, and visitors alike.

Every aspect of the renovation has been carefully considered to balance both functionality and the user’s experience—integrating sustainability, wellness, and biophilic design to achieve the AIA’s vision—and the façade’s frit pattern is no exception.

Here, we are pulling back the curtain on the iterative design process for these patterns and the inspiration behind them.

What is a frit pattern?

A frit pattern is a design, from simple dots or lines to complex custom patterns, applied to transparent surfaces such as exterior windows or interior window walls. The frit pattern is created by applying an enamel coating, either through silk-screening or ceramic digital printing. Frit patterns serve critical functions, including reducing solar glare, minimizing heat gain, and supporting bird-friendly architecture. When thoughtfully designed, these patterns can create a captivating interplay of light—filtering and dappling sunlight in ways that mimic natural light filtering through trees. This effect is not purely aesthetic; frit patterns enhance user wellbeing by creating impactful biophilic connections to daylight and nature.

With my background as an artist, I have a deep appreciation for the creative process behind these patterns—a process that merges traditional printmaking with modern design technologies. To me, there is an appealing tension between the design aesthetics and technical, sustainability performance targets. This balanced approach brings warmth and depth to architectural design by infusing the process with artistic methodologies.

Design goals for the AIA HQ frit pattern

For the AIA headquarters, we aimed to design a unique, custom digital frit pattern that delivered on all fronts—performance, wellness, and aesthetics.

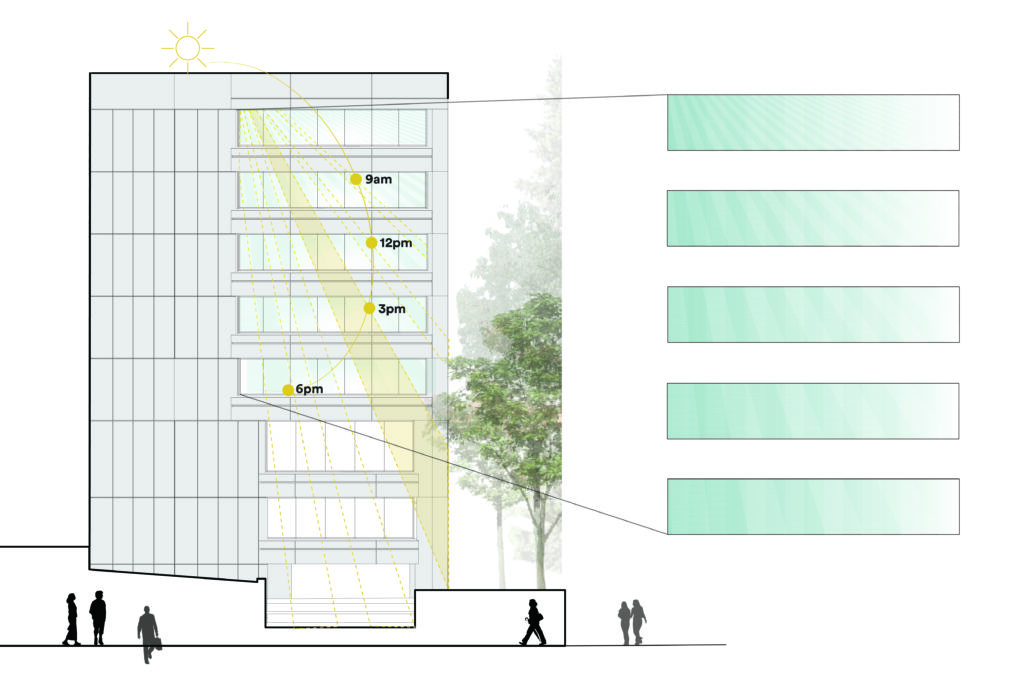

The external plaza-facing sunshade system contains 302 PV panels with applied frit that addresses the glare and solar heat gain into the workspaces. The street-facing frit will span five levels of the building’s façade (floors 3 through 7) and is applied directly to the glass. The frit patterning for both the PV panels and the street-facing glass is designed to enhance the sensory and biophilic experience throughout the interior and across the building’s façade with dappled light and shading. The graphic expression creates a sense of movement and time while maximizing thermal comfort and energy production.

This extensive patterning plays a crucial role in shaping the building’s visual identity, and it was developed in close collaboration with the entire project team to ensure it aligns with our client’s goals.

A peek into the process

Concept Validation: Creating the Macro Pattern

In the first phase, I generated a macro pattern that mapped the frit pattern’s location and density across the building’s glass façade and PV panels.

The macro pattern on the PV arrays drew inspiration from Washington, D.C.’s rich history and unique elements, including dappled light from the abundant tree canopy and Brutalist architecture. Our design drew from The Architects Collaborative (TAC), the original architects of the AIA Headquarters. TAC’s initial plans for triangular waffle slabs and stairwells, inspired by the site’s irregular geometry, informed a PV frit pattern that reflects the building’s unique site and history.

For street-facing façades, the movement of the sun across the building was our major design driver: by tracing the path of the sun’s rays across the building, the pattern brings the Brutalist structure in tune with its context, while creating a welcoming, sweeping gesture toward the site.

I was personally inspired by the Washington Color School, an abstract expressionist movement from the 1950s-1970s, concurrent with the design of the original AIA Headquarters. Artists from this movement, such as Sam Gilliam and Alma Thomas, engaged with the city’s architecture through printmaking, painting, and patterning techniques. In Gilliam’s “Shoot Six,” beams of color evoke energy and empowerment, while Thomas’s “Cherry Blossom Symphony” and “White Roses Sing and Sing” depict the city’s flowers with harmonized light and texture.

While these inspirations sparked our creativity, the primary focus was ensuring that the design concepts met the AIA’s ambitious performance goals.

Collaborating with the client and design team, we distilled these inspirations into coherent design concepts. To reduce solar glare and heat gain, we needed the frit density to achieve 60% density coverage on the street-facing glass façade. Using Enscape and Lumion, I studied sunlight and shadow movement by following the sun’s path across the exterior throughout the day and year. The macro pattern on the street-facing façades was developed to be densest in high sun exposure areas and sparser in areas where visibility was crucial for occupants and visitors.

We utilized software like Illustrator, Photoshop, Revit, Rhino, Grasshopper, and Lumion for iterative studies and client validation. By extensively modeling the frit patterns, we tested various scales and densities, visualizing the pattern from multiple viewpoints, both inside and out, across different seasons. This comprehensive approach ensured the design met aesthetic and performance requirements.

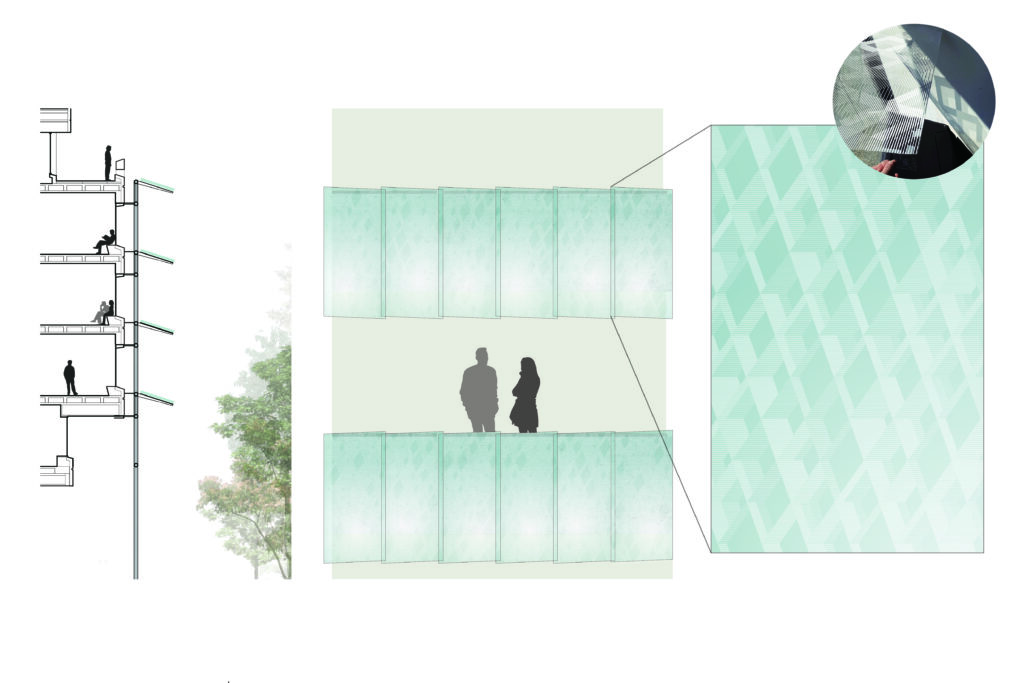

Design Iteration: The Micro Pattern

Once the overall concept and macro pattern for the street-facing façade glass and the PV panel system were approved and finalized, we began exploring options for the micro fill pattern and density. This process involved testing various micro fill patterns through physical mockups. We printed the patterns in white ink on acetate at scale to study their appearance and dappled light qualities. These acetate prints were installed on office windows, a mockup PV panel, and eventually on site at the AIA HQ in DC.

For the PV micro pattern studies, it was crucial to understand how the pattern interacted with the PV grid lines. We designed a grid pattern that mimicked the PV grid’s appearance, printed it on acetate, and mounted the sheets to a plexiglass panel half the size of our PV panels. We explored a range of lines, dots, and custom shapes for the micro pattern options. Given the complexity of the patterning, we determined that a digital frit application would be the most cost-effective for both the street-facing glass and PV frit.

Performance Validation

Performance validation focused on ensuring the PV frit pattern would produce clear, crisp shadows across the building’s exterior and interior. The micro frit pattern was modeled in Rhino to study dappled light qualities and confirm the scale and density of the final pattern. Each panel featured unique frit densities and openings to create dappled light reminiscent of the surrounding trees and nature. Various line density combinations and openings filled the overall diagrid pattern, with diamond sizes and openings optimized for light and shadow.

As we refined the micro pattern for the PV panels, we applied the same logic to the street-facing glass. The linework scale was similar, and both patterns were designed to harmonize, unifying the dappled light experience throughout the building’s interior. The street-facing frit pattern responded to the building’s unique geometries, while the PV shading frit pattern sourced the building’s geometries to produce a dynamic light quality, enhancing the façade and interior experience throughout the day.

Fabrication

Throughout the design process, we communicated regularly with our fabricating partners: Onyx for the PV frit and Viracon for the street-facing frit. Before fabrication, we collaborated with both to produce physical sample mockups for internal and client review, a crucial step in design validation. This ensured we met technical requirements and project goals. We documented the macro pattern in Revit and Rhino, finalized it in AutoCAD and Illustrator before fabrication.

Next Steps

The street-facing fritted glass has been fabricated and is being installed on site, and the PV panels will soon go into fabrication. As we move ahead, we look forward to seeing how these innovative frit patterns transform the AIA Headquarters, blending art, architecture, and sustainability in a way that honors the building’s legacy while paving the way for its future.

Our team

Client: AIA

Architect: EHDD

EHDD Façade and Frit Design Team: Jeemin Bae, Eilish Cullen, Katherine Miller, Rebecca Sharkey, Christian Wopperer, Lily Yao

General Contractor: Turner Construction

Local Architect: Hartman-Cox Architects

Local Consultant: Custom Glass

Fabrication: Viracon, Onyx Solar

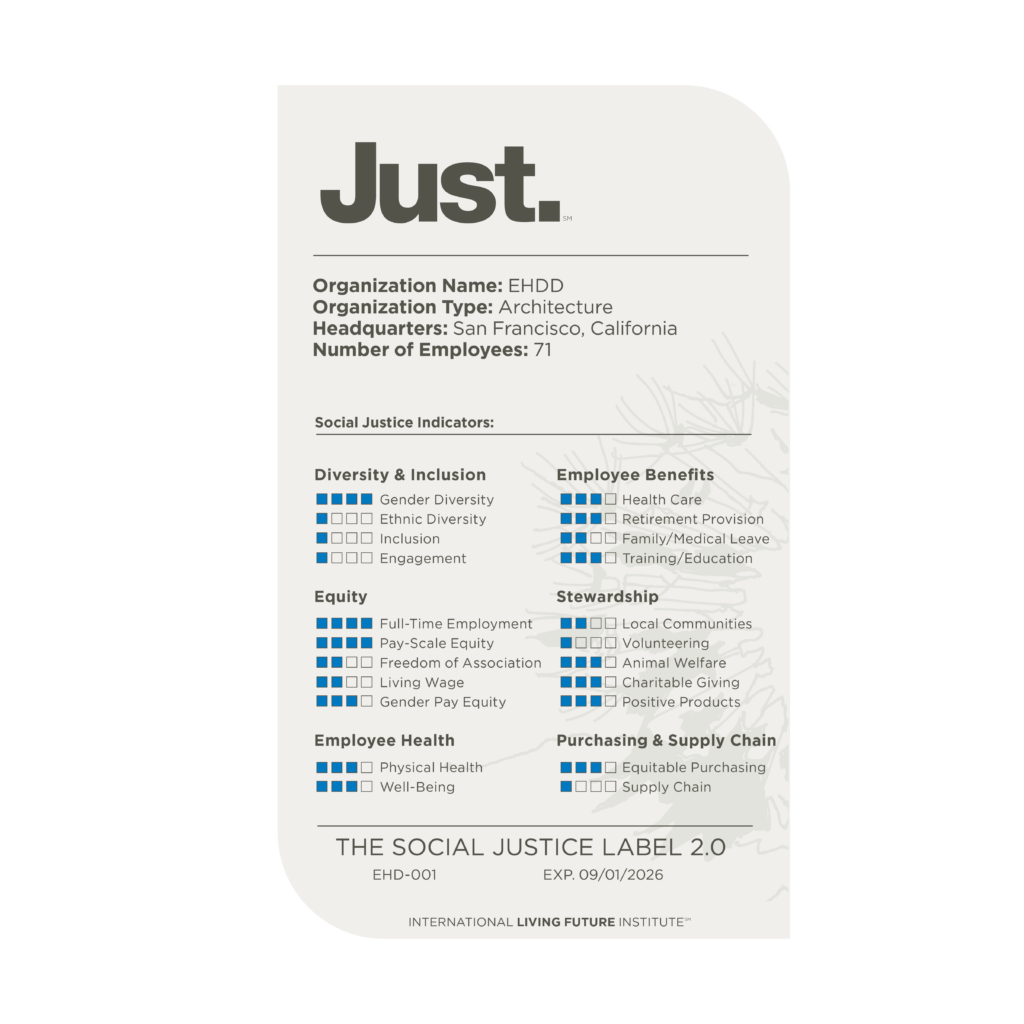

EHDD Earns Just 2.0 Label: Our Commitment to Equity, Transparency, and Social Justice

EHDD is proud to join more than 200 organizations around the world who are demonstrating their commitment to fair employee treatment, responsible financial investments, and positive community engagement through the International Living Futures Institute’s Just 2.0 Label initiative. As a firm dedicated to creating transformative places of belonging and impact, our participation in ILFI’s Just Label is an extension of our mission and core values.

“Just 2.0 is more than a label—it’s a comprehensive assessment of our business practices that reinforces our dedication to fostering diversity, equity, and inclusion as essential components of EHDD’s identity,” said Jennifer Devlin-Herbert, EHDD Principal and CEO.

“This process has been an opportunity to reflect on our practices, identify areas for growth, and make lasting improvements that benefit our people, clients, and communities,” said Kerry Lange, Director of People and Culture.

What is the Just 2.0 Label?

Created by the ILFI, the Just 2.0 Label helps organizations create meaningful policies and ensures that those policies create growing positive impact over time. The Just label is a voluntary disclosure tool for organizations that acts as a transparency framework, rather than a certification program.

To earn a Just 2.0 Label, EHDD reported on indicators related to our operations and employees. Our performance was evaluated by clear, measurable goals across four areas, then summarized in our label and shared transparently to the public Just database.

Turning Practices into Policies

For EHDD, this process was an opportunity to reflect on the core values of Curiosity, Courage, Care, and Community that have emerged throughout our 75-year history. Furthermore, it empowered us to transfer our long-held values and ongoing practices into clear policies with measurable metrics:

- Formalizing Pay Equity Policies: We formalized our Gender Diversity, Ethnic Diversity and Pay Equity policies to support our current practices and ensure that our commitments can be measured and improved upon.

- Strengthening Diversity and Inclusion Initiatives: EHDD prides itself on being a diverse and inclusive workplace, and we look forward to continuing initiatives that support underrepresented groups and promote inclusivity at every level of the organization.

- Reinforcing Our Commitment to Responsible Investment: Financial responsibility is a key component of the Just 2.0 framework. As part of our certification process, we’ve evaluated our investments to ensure that they align with our values and contribute to positive social and environmental outcomes.

As we move forward, we’re dedicated to pushing our boundaries, learning from our experiences, and setting a positive example in the architecture and design industry. For more information about the Just 2.0 Label and its framework, visit the International Living Future Institute.

Designing the aquarium of tomorrow: Lessons from four unique projects

By elevating the unique culture and context of each project, architects can build curiosity, connection, and a passion for conservation into their designs.

This article was originally published by the Seattle DJC. Read it here.

It came earlier than I anticipated — a phenomenon I suspect is felt by architects around the world who step both feet into a specialized building type. You visit the precedents, and you start to see the patterns. The “best practices” and “must haves” of the past become overbearing trends. Every time you visit that type of project and see the same design ideas repeated, you feel a building sense of urgency to do something different. For me, as I worked on aquarium projects, it was two things. One was the tension between these institutions that champion environmental stewardship, while most of the facilities use more energy than any other building type. The other was the relentlessness of the black box experience.

Today’s institutions feel it, too. They ask, “What is the future of aquarium design?” I would suggest that the answer is twofold: getting serious about climate change and leaning into the unique aspects of institutional culture and context. Comparing four of EHDD’s recent aquarium projects shows how leveraging the unique culture and context of each project allows it to self-differentiate and break away from the tired black box formula.

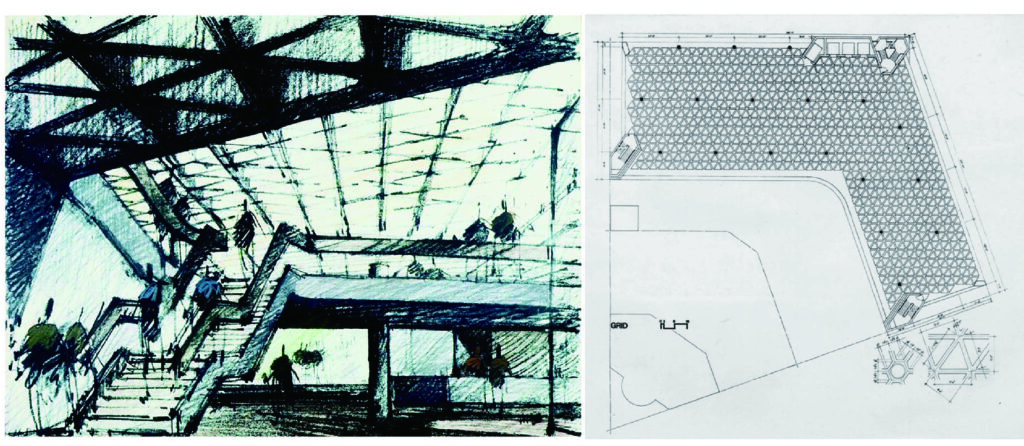

Toledo Zoo Aquarium Improvement Project

The first aquarium I worked on was a renovation of an existing facility in Toledo, Ohio, embedded in their local zoo. As we wrapped our arms around the project’s ambitions, exploring building sites alongside the Maumee River, we learned that while the exhibit itself was an outdated, repetitive row of small blue boxes, literally falling to pieces after years of unmitigated corrosion, the building itself was a beloved heirloom to the local community. It quickly became clear that this was the key to the project. Revitalizing the existing building offered benefits across a triple bottom line: It would help us shift the slim $20 million budget from construction sitework to creating more dynamic exhibits; it would reduce the project’s embodied carbon; and it would send a clear message of reinvestment in the community and the heart of the Works Progress Administration-era zoo campus.

While the shell had become sacred, the interior was anything but. We looked to create a completely transformed visitor path, restoring the long-abandoned central entry, quadrupling the volume of the exhibits, creating larger tanks that offered multiple viewing experiences, and introducing variety and hands-on experiences. Delivering this level of visitor experience within a defined envelope was like working on a Swiss watch, but our space constraints allowed us to explore a low-energy drum filtration technology, due to the reduced footprint it required.

Pacific Seas Aquarium

At our next aquarium project, we built on the low-energy technology we beta-tested in Toledo. Tacoma’s Point Defiance Zoo wanted to set a new bar for sustainability in aquarium design. This group’s commitment to conservation was unparalleled, and they wanted to walk the walk as we approached the design of their new Pacific Seas Aquarium.

Achieving these significant ambitions meant leaning in to the vertical nature of our steeply sloped site. Our design arranged the water treatment systems to take advantage of gravity, instead of expending energy by pumping multiple times. Beyond this, we used every tool in the book — onsite rainwater capture and re-use, a mass-timber structural system to reduce embodied carbon, and of course, all-electric systems— to deliver the most sustainable aquarium in the country.

The project uses digital personalized engagement at the start and finish of the experience to compel visitors to make individual commitments to actions that help them support ocean health. To emotionally anchor these commitments, and to help visitors register the mostly regional aquatic collection as part of their local environment, we interlaced the visitor path with views to the pine-fringed hillside.

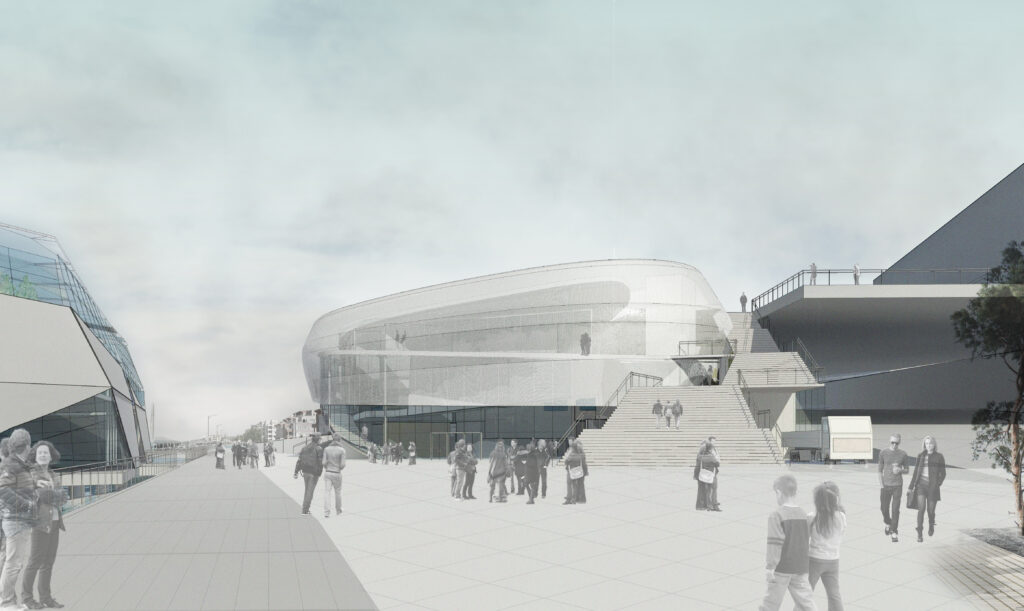

Seattle Aquarium Concept Design

Leveraging the immediate context to flavor the visitor experience played heavily in the campus plan and concept design work we completed for the Seattle Aquarium in 2016. Looking out toward the Olympic range, the Seattle Aquarium has perhaps the most spectacular waterfront view of any existing aquarium. But despite the beauty of its waterfront location, the building is sited in a deeply urban context. Still, we saw this as an opportunity to tell an enhanced story of conservation.

Embracing the urban site, we located the new Ocean Pavilion across the promenade where it would be anchored to the fabric of the waterfront revitalization. This single move yielded opportunities to create visual connections that highlight the urban/natural interface, showing how humans have impacted all aspects of the environment. From a civic perspective, the building becomes a focal point — the jewel sitting at the nexus of the waterfront promenade. It offers many opportunities for generosity to the public — spectacular views from the accessible roof deck, a graceful pedestrian descent from Pike Place Market down to the waterfront, and interpretive opportunities outside the paywall. We’re excited to see that many of these ideas have survived in the design as executed by LMN Architects, and look forward to visiting when it opens this fall.

Sobela Ocean Aquarium

Our most recent aquarium was a very different animal than the Pacific Northwest projects. The Sobela Ocean Aquarium, located on the campus of the Kansas City Zoo, is a 72,000-square-foot, ground-up facility that features 650,000 gallons of water and a broad survey of marine life from sand tigers to nudibranchs. Our charge here was to deliver “wow” — to create an indoor, all-season experience that would draw visitors to the zoo campus all year long.

Deep in the heart of the Midwest, we quickly realized that visitors here come from a different starting point. Many will never visit the ocean, and few will be tuned into the critical role it plays in our climate. This facility was a unique chance to build in them a passion for and connection to the ocean.

To do so, we orchestrated the visitor path to evoke the experience of the ocean, leveraging sensory cues such as light quality, temperature, spatial volume, and sound to foster the emotional bonds built when having the experience in real life. It’s an experience that unfolds to meet you at a human scale, and surprises you with a dynamic, pulsing wave tank, the moment you enter. Overlaid as an interpretive framework: the storyline of ocean currents as the superhighway that interconnects all ecosystems. This storyline ties together a disparate animal collection and is a backbone to showcase the ocean as the key player in the health of our environment.

Every project has its challenges. For the Sobela Ocean Aquarium, it was the COVID-19 pandemic. Our client group had given us the freedom to make the project as sustainable as possible, so long as the measures fit within the budget. As admitted climate warriors, we took this charge, seeking every opportunity to stretch the project performance past our LEED Silver baseline.

Then the wild inflation of 2021 hit. Wood prices were up. Electrical switch gear was up. PVC piping doubled in cost over a month. To keep within arm’s reach of our $61 million construction budget, we had to make some hard decisions. Among these was the return to gas boilers — a hard pill to swallow. In the year since this project opened, I’ve made my peace with it. Our team worked hard to make all-electrical systems cost competitive, and by stretching toward this goal, we delivered a project that really tightened up its energy usage. The truth is, the electrical grid in Kansas City is still fully reliant on fossil fuels; I take solace in the idea that, as it improves, the project we’ve delivered will easily adapt to an all-electric future.

EHDD has been designing aquariums for 40 years. Our journey, starting with Monterey Bay Aquarium, has been characterized by a willingness to challenge the status quo, a tendency to embrace unique cultural and environmental contexts of each project, and a commitment to do right by the environment. As we look toward the “Aquarium of the Future,” it’s clear that elevating the unique aspects of each project is the key to fostering curiosity, connection, and responsibility to the environment that is core to the mission of this industry.

Making landscapes memorable

Cultivating a close connection between the natural and curated planted environment and park architecture is as essential as blurring the boundaries between them.

This article was originally published by the Seattle DJC. Read it here.

EHDD has been working in close collaboration with communities, public agencies and our design partners on notable landscape projects across the Northwest for the past 20 years. As the design lead for these projects, I set out with one clear goal when working with clients and communities on their beloved parks: to create a memorable landscape.

We have found that simple, iconic forms, constructed of locally sourced materials, resonate with our special Pacific Northwest environments, especially in park settings. Memorable landscapes result from a close connection between the natural and curated planted environment of a park and the park architecture; we constantly strive to blur those boundaries to create a cohesive experience.

A particular specialty of EHDD is working on waterfront parks in the Northwest. These complex sites involve layers of environmental regulation and restoration, as well as the rehabilitation of the most memorable public spaces linking our cities to Puget Sound. From Percival Landing in Olympia to Juanita Beach Park in Kirkland, EHDD’s waterfront park teams have been fortunate to collaborate with local communities to create these memorable landscapes.

We have two distinct points of departure in our design process. First, we are committed to utilizing locally sourced materials in our parks projects. This strategy greatly reduces the carbon footprint of the project. When sourced from sustainable forests, locally sourced wood materials not only avoid carbon emissions from cross-continental shipping, but also have a climate positive impact by storing carbon in the wood.

Economically, this practice supports local jobs and trade economies. Even in places where these trades are struggling, the choice to use local trades whenever possible will boost those economies over time.

It also makes sense from the owner’s point of view: While costs may be comparable to other building materials, prefabricated wood solutions like cross laminated timber (CLT) can save money by shortening construction time. Utilizing Pacific Northwest wood products supports our local and regional economies while at the same time integrating the structures with our environment.

The Bathhouse at Juanita Beach is clad in locally sourced cedar with a natural finish which weathers over time. The picnic shelters are constructed of CLT panels (think of large, solid wood panels, layered to form large structural elements that can span twelve to sixteen feet between supports) which are also locally sourced.

Our parks projects have also featured prefabrication strategies that greatly reduce the duration of construction, allowing the parks projects to open during the peak summer season. We have utilized prefabricated CLT panels at the recently completed Lake Sammamish State Park and at Juanita Beach Park. The use of these prefabricated, locally sourced wood elements is also a demonstration for the general public to see how these new building technologies can be utilized to create healthy, environmentally integrated structures in our communities. In my practice, I’ve found that locally sourced wood brings a unique warmth and character to buildings, grounding them in their specific landscapes. Whether it’s a building in the rolling hills of Goldendale or along the vibrant shores of Seattle, local materials anchor a structure in its setting, creating a special sense of space.

Second, when designing park projects, EHDD curates the visitor experience by integrating and coordinating the landscape architecture, architecture and the interpretive design content. By bringing the full design team together at the beginning of the project to work with the client and the community, we can intertwine landscape concepts with architectural concepts and strengthen those relationships with the interpretive story. This results in richer, layered environments and a more authentic visitor experience.

We are constantly working at blurring the boundaries between the built environment and the natural environment. At Goldendale Observatory State Park, it was important for the operational needs of the park to provide a self-guided visitor experience in tandem with the staffed park programming. Working with Walker Macy, the landscape architect, and C&G, the interpretive designer, EHDD developed pathways around the observatory building that visitors can explore upon arrival and between park programs. These landscape journeys provide views of Mt. Hood, the Columbia River Valley and the surrounding mountains. Interpretive content along the pathways describes the surrounding environment and introduces themes that are presented in more detail inside the observatory.

By integrating the design team, featuring locally sourced materials, and implementing prefabricated construction techniques, we can achieve a sense of wonder and that “ah-ha” moment that enhances our favorite Pacific Northwest environments.

Team selected to design affordable housing for educators amid California’s escalating cost-of-living crisis

SAN FRANCISCO, CA – In response to the escalating cost of living in California, particularly in Santa Cruz —one of the nation’s most unaffordable housing markets—a collaborative design-build team of Bogard Construction, EHDD, and Studio VARA has been chosen to design affordable housing units specifically for educators. This project will address the growing challenge of retaining talented educators within school districts where living costs are soaring.

“Educator housing is a game-changer, both for the families who will live in these homes, as well as communities like Santa Cruz whose essential services are now threatened by the glacial pace of housing development over the past decades,” said Brad Jacobson, EHDD principal in charge for this project.

“It’s no secret that Santa Cruz has an affordability issue, as well as a housing crisis, which makes retention of our teachers and education staff extremely challenging. Santa Cruz City Schools is making a tremendous step by building housing for our valued educators. Being local to Santa Cruz, the pressing need for this project is very clear to our team, and we are honored at the trust that the SCCS District has placed in Bogard to successfully deliver,” said Jared Bogaard, president of Bogard Construction.

The proposed development is a multi-story, multi-family complex consisting of 100 units, offering a diverse mix of studios, one-, two-, and three-bedroom apartments. The design will reflect and take advantage of the coastal Santa Cruz environment to create a vibrant, resilient community where educators and their community can thrive.

“Educator and workforce housing are the new frontier, filling the ‘missing middle’ between subsidized affordable housing and market-rate developments, and Studio VARA is honored to have this opportunity to bring our deep experience in multifamily housing to the team,” said Christopher Roach, principal at Studio VARA.

This project is backed by the 2023 approval of Measures K and L by Santa Cruz City voters, securing $371 million for Santa Cruz City Schools. This funding is allocated for school updates, repairs, and the construction of affordable rental housing for school staff. The project’s vision extends beyond immediate housing solutions, aiming to support educators in eventually purchasing their homes through bond-sponsored grants, thus fostering long-term educator retention.

Santa Cruz’s project joins a growing list of similar initiatives in California after the state passed a series of bills making it easier for school districts to provide affordable housing specifically for district employees and their families. Los Angeles Unified and Santa Clara Unified school districts were the first to complete such projects in the state. Recent projects include a 122-unit complex in Daly City’s Jefferson Union High School District and a 135-unit complex by the San Francisco Unified School District. A collaborative effort in Palo Alto involving several school districts and non-profits is underway to construct a 110-unit complex.

As these pioneering projects unfold, valuable insights and best practices will emerge, guiding other districts keen on adopting similar strategies. The Santa Cruz project is not only a housing solution, but a blueprint for sustainable educator support and community building in California’s challenging economic landscape.

About EHDD

EHDD is an award-winning architecture firm with a strong commitment to advancing climate action through sustainable design. With decades of experience helping clients achieve their dreams, EHDD creates transformative places of belonging and impact.

About Bogard

Bogard Construction is a family-owned and operated construction firm, based in Santa Cruz, specializing in many project types and delivery methods throughout California. With over 77 years of experience, spanning four generations of family members, Bogard is an active advocate for the success of each of our projects.

About Studio VARA

Studio VARA is an interdisciplinary design studio driven by a passion for excellence in design, service, and execution across a wide range of project sizes and typologies that align with our mission to build a better world for our clients, our community, and our planet. We are a minority woman-owned firm based in San Francisco’s Mission District with roots deep in the Bay Area design and construction industry, and a deep commitment to empowering designers as agents of positive change in our built environment and society.

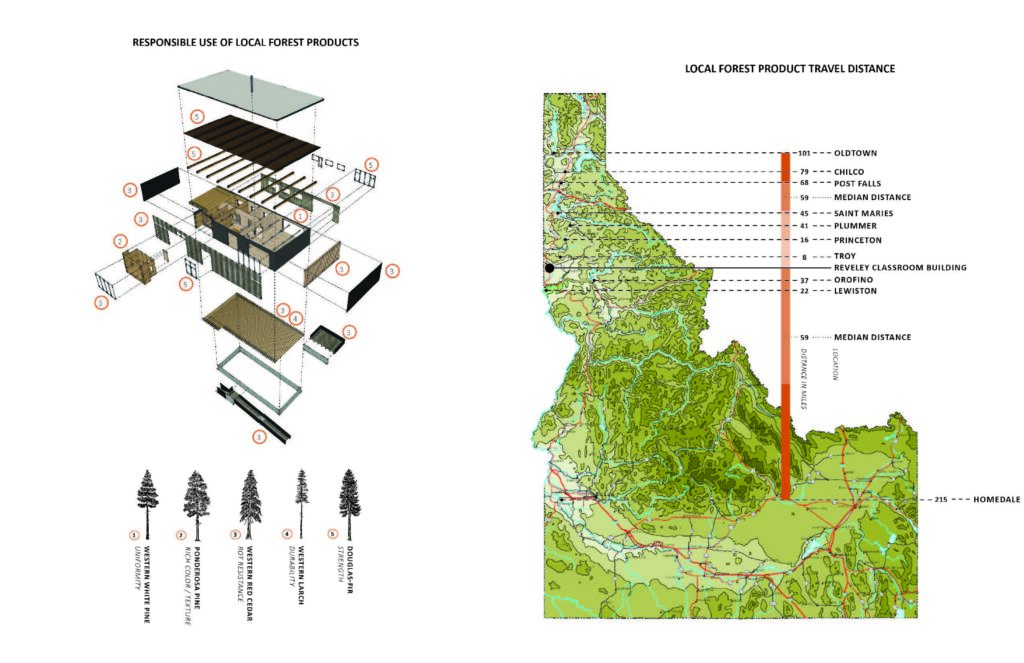

Architects, Drop the “Catalogue” Mindset and Specify Locally Sourced Timber

PUBLISHED: FEB. 1, 2024

Growing up in a mill town in Northern Idaho, I could hear the low rumble of lumber mills along the Spokane River as I fell asleep. There were seven mills downriver of Coeur d’Alene then. Now, there are none. As one mill after another shut its doors, the community grappled with the loss of this vital trade and the jobs it supported, shaking its fists at the economic forces seemingly so far beyond our control. At the same time, I saw new buildings in Coeur d’Alene being constructed of brick, with steel structures and glass facades, materials shipped in from across the globe, with no discernable connection to our community.

This pattern was mirrored globally as the industry pivoted to steel and concrete, sourced from afar without regard for the resources available locally. This change has had significant repercussions, destabilizing local trades and contributing to environmental degradation through increased carbon emissions and resource depletion. This way of sourcing materials has resulted in a building stock wholly divorced from its local environment.

In recent years, we’ve started finding our way back through the re-acceptance of wood as a viable building material. Industry leaders, through advocacy and research, have proven wood’s viability — highlighting its strength, fire resistance, and environmental benefits.

True transformative potential, however, lies one step further, in embracing locally sourced wood.

No single strategy will positively impact the architecture profession more than simply considering where our building materials come from. From energy efficiency to carbon footprint to longevity and health of buildings, locally sourced materials offer the greatest potential to return to a timeless way of building.

No single strategy will positively impact the architecture profession more than simply considering where our building materials come from.

The Case for Locally Sourced Wood

When sourced from sustainable forests, locally sourced wood materials not only avoid carbon emissions from cross-continental shipping, but they can also have a climate positive impact by storing carbon in the wood. Economically, this practice supports local jobs and trade economies. Even in places where these trades are struggling, the choice to use local trades whenever possible will boost those economies over time. It also makes sense from the owner’s point of view: while costs may be comparable to other building materials, prefabricated wood solutions like cross laminated timber can save money by shortening construction time.

In my practice, I’ve found that locally sourced wood brings a unique warmth and character to buildings, grounding them in their specific landscapes. Whether it’s a building in the rolling hills of Santa Cruz or along the vibrant shores of Seattle, local materials anchor a structure in its setting, creating a special sense of space.

Making It Happen

The shift back to local sourcing requires a fundamental change in mindset. It’s about looking beyond the pages of a catalogue and taking stock of the environment that surrounds us.

This was a lesson I learned while working on the Revelry Classroom Building at the University of Idaho. Our client was adamant that only Idaho forest products could be used in the creation of this building. This reframed the specification process for me, forcing me to look around to the natural forests and manufacturers. Working in collaboration with Idaho wood industry partners, our design team used locally produced wood materials throughout, including FSC- and SFI-certified framing lumber, cedar siding, engineered wood I-joists and glulam beams. We harvested Western Larch from the University of Idaho’s experimental forest, dried it in university kilns, and milled it for the flooring. Interior walls were clad with veneered wood panels, each highlighting a particular Idaho wood species. In the end, our materials traveled an average of 70 miles from source to project site.

Building relationships with local manufacturers and mills is crucial. By understanding the qualities of each material, designers can make informed decisions about their use in different aspects of a project.

At EHDD, we are forming partnerships with regional mills and west coast-based mass timber fabricators to highlight the value and potential of our locally produced materials. We’ve had success specifying local materials on both public and private projects; while publicly bid projects require more rigor to source multiple options for materials, it can be done, and done within budget.

Our Western Yacht Harbor project in Seattle exemplifies this approach. As Seattle’s first modern Dowel Laminated Timber (DLT) building, we put in the time to build connections with local manufacturers and better understand the characteristics of their materials. The use of hardwood dowels in DLT not only reduces the carbon footprint but also provides a stable, resilient structure, perfectly suited to Seattle’s commitment to innovative design.

In another example, EHDD recently designed the UC Santa Cruz Coastal Biology Building, a new 40,000 sf building serving the university’s world-class marine and ocean health research, education, and public service facility. Located along the Pacific Coast, we sought local timber that could withstand the harsh coastal climate, while exemplifying the region’s character. Working with local manufacturers, we learned about Western Red Cedar, which was used on the exterior. This material is a defining characteristic of the final building and will serve the university for years to come.

The journey back to local sourcing in architecture is not just a nod to the past—it’s a necessary step toward a sustainable future. By reconnecting our buildings with their local roots, we create spaces that are not only environmentally responsible, but also deeply resonant with the communities they serve. As architects, we have the responsibility to lead this change.

As EHDD CEO Jennifer Devlin-Herbert at the 2023 AIA Keynote Panel, “architects control the spec book.” It’s not just about specifying wood; it’s about knowing where the trees were grown, who milled it, how far was it delivered? These questions, when applied to all building materials, will move us toward more sustainable building projects, positively impacting our communities and regions.